Subsection 256(1) - Associated corporations

Paragraph 256(1)(a)

Cases

The Queen v. W. Ralston & Co., 96 DTC 6488 (FCTD)

100 voting common shares of the taxpayer were held by members of the Cohen family, and the 100 voting preferred shares of the taxpayer were held as to 50 shares by the son of the Cohen's solicitor as to the other 50 preferred shares, by the solicitor's secretary. The taxpayer was not controlled by the Cohens, with the result that it was not associated with various corporations that were controlled by the Cohens.

Harvard International Resources Ltd. v. Provincial Treasurer of Alberta, 93 DTC 5254 (Alta. Q.B.)

The taxpayer held an undivided 99.328% interest in the 100 outstanding common shares of a corporation ("Holdings") and another corporation ("Energy") held all the other outstanding shares including 150 voting preferred shares. In response to a submission of the provincial Crown that the taxpayer was associated with Holdings for purposes of s. 26.1 of the Alberta Corporate Tax Act (which applied the test in s. 256(1) of the federal Act as it then read) on the basis that under the terms of a shareholders agreement the taxpayer effectively had the right to cause Holdings to redeem the shares held by Energy upon the termination by the taxpayer of an agreement for the provision by Energy of certain management services to a partnership, Hutchinson J. found that such rights of the taxpayer were "not to be found within the confines of Holdings' charter and by-laws where the real test of de jure control must be found" (p. 5265). Accordingly, Holdings was controlled by Energy and not by the taxpayer.

The Queen v. Imperial General Properties Ltd., 85 DTC 5500, [1985] 2 CTC 299, [1985] 2 S.C.R. 288

The Wingold group held 90 common shares of the taxpayer and the Gasner group held 10 common shares and 80 voting cumulative preference shares with a nominal par value and the entitlement, upon the winding-up of the taxpayer, to receive that par value plus any accumulated but unpaid dividends. Since the corporate charter also provided that the taxpayer would be wound up upon a resolution for that purpose supported by 50% of the voting rights in the company, and the Wingold group thus had "the right to terminate the corporate existence should the presence of the minority common and preference shareholders become undesirable", the Wingold group controlled the taxpayer.

Allied Farm Equipment Ltd. v. MNR, 73 DTC 5036, [1972] CTC 619 (FCA)

Given that s. 39(4) of the pre-1972 Act applied only for the purposes of s. 39, which provided a reduced rate of tax for certain Canadian corporations, s. 39(4) did not make each of two Canadian-resident corporations associated with a U.S.-resident corporation, with the result that the two Canadian-resident corporations were not deemed by virtue of s. 39(5) to be associated with each other.

Donald Applicators Ltd. v. MNR, 69 DTC 5122, [1969] CTC 98 (Ex Ct), briefly aff'd 71 DTC 5202, [1971] CTC 402 (SCC)

498 Class B shares in the capital of each of ten companies was held by a corporation ("Saje") and 2 Class A shares were held in each corporation by two unrelated persons who, in each case, were Bahamian lawyers who did not hold shares in any of the other nine companies. The Class B shares carried the right to vote on all questions except the election of directors (who were the relevant Bahamian lawyers) and the Class A shares had full voting rights, including the exclusive right to vote on the election of directors. The net yearly profits of the company were required to be distributed each year in cash, and no shares could be issued by the directors without the unanimous consent of the existing shareholders.

All ten companies were controlled by Saje for purposes of s. 39(4)(a) of the pre-1972 Act in light of the fact that the Class B shareholders had the voting power to change the articles of each company, and thereby had the ultimate power to change the directors. Although in a situation where "the directors had been shorn of authority to make decisions binding upon the company and such decisions had been reserved for the shareholders in general meeting", the ordinary rule, that control resides in the voting power to elect directors, might not apply, here, the dividend and share-issuance restrictions did not constitute a substantial restriction on the powers of the directors.

MNR v. Dworkin Furs (Pembroke) Ltd., 67 DTC 5035, [1967] CTC 50, [1967] S.C.R. 223

Dworkin Furs Ltd. owned 48% of the issued shares of Dworkin Furs (Pembroke) Limited in its own name and 2% in the names of Roy Saipe and Helen Saipe as its nominees, with the other 50% being owned by Sadie Harris. In light of the test of de jure control enunciated in the Buckerfield's case (64 DTC 5301 at 5303), in these circumstances Dworkin Furs (Pembroke) Limited was not controlled by Dworkin Furs Ltd. for purposes of s. 39(4)(a) of the pre-1972 Act.

See Also

Kruger Wayagamack Inc. v. The Queen, 2015 TCC 90

The taxpayer was capitalized, and its common shares then were held, on a 51-49 basis, by a business corporation ("Kruger") and a Government of Quebec corporation ("SGF") in order to acquire, modernize, and operate a sawmill business. Under a unanimous shareholder agreement ("USA"), Kruger was entitled to elect three of the five directors. The taxpayer was not entitled to refundable investment tax credits if it was associated with Kruger by virtue of s. 256(1)(a).

Jorré J ultimately found that s. 256(1.2)(c) applied so that Kruger was deemed to control the taxpayer for purposes of s. 256(1)(a). However, before so concluding, he found that, under the USA, Kruger had "operational," but not "strategic," control of the taxpayer so that it thus lacked de jure control. The USA required unanimous approval by the board (with at least one of SGF's directors included) or of the shareholders for a wide range of matters – including of the capital and operating budgets and changes thereto, business plans or departures therefrom, the hiring or dismissal of various officers or payment of bonuses, any significant financing or security interest grant, and any entering into or changes in various significant contracts. (On the other hand, decisions on various operations matters could be made by majority decision.)

Kruger's inability to make strategic decisions meant that it did not have a "dominant influence in the direction of the appellant," as per Langlois (paras. 65-66).

In considering whether Kruger had de facto control, reference also could be made to non-USA agreements, namely, for the provision by Kruger of management services, and the marketing by it of the taxpayer's products, including the sale of wood pulp to Kruger itself, as well as to Kruger's specialized industry knowledge. However, these were not enough to establish de facto control, given significant built-in restrictions in those agreements and given the significant role of SGF.

See summary under s.256(1.2)(c).

Administrative Policy

1 February 1999 T.I. 982371

It is generally the Department's view that a foreign corporation is a 'person' for purposes of the Act unless the context clearly indicates otherwise." Accordingly, for purposes of applying the personal services business rules, a Canadian corporation was found to be associated with a U.S. corporation that it controlled.

23 June 1995 T.I. 951047 (C.T.O. "Associated Corporations")

Where a corporation ("Supplyco") owns 50% of the shares of another corporation ("Distributorco") which is a franchisee of Supplyco, Supplyco will be considered to control Distributorco where Distributorco is economically dependent on Supplyco as a single supplier.

1993 APFF Roundtable, Q.1

Where a wholly-owned subsidiary ("Holdco II") of Holdco I is the sole general partner of three limited partnerships which, in turn, each hold 1/3 of the shares of Opco, Opco will be considered to be controlled by Holdco II (and therefore associated with Holdco I) - even though the general partner interest of Holdco II is not sufficient to deem a sufficient number of Opco shares to be owned by Holdco II so as to give rise to control by Holdco II - given that Holdco II appears to have de jure control of Opco. General partners are the sole persons authorized to administer a limited partnership, and it is assumed that Holdco II is able to vote for the members of Opco's board of directors.

IT-64R3 "Corporations: Association and Control - after 1988".

Paragraph 256(1)(b)

Cases

Southside Car Market Ltd. v. The Queen, 82 DTC 6179, [1982] CTC 214 (FCTD)

"[S]ince the language of paragraph 256(1)(b) sets forth two distinct circumstances when two corporations are associated, namely, when controlled by (1) the same person and (2) by the same group of persons, the two sets of circumstances are mutually exclusive." In other words, the mention of a "person" and a "group of persons" impliedly excludes a combination of the two. Accordingly, S.256(1)(b) does not cover the situation where Corporation A is controlled by an individual and Corporation B is controlled only by a group of which the individual is a member.

The Queen v. Mars Finance Inc., 80 DTC 6207, [1980] CTC 216 (FCTD)

It was stated, obiter, that where the Court has to decide whether two corporations are associated by reason of being controlled by the same persons or same group of persons, who might be complete strangers and not persons all related by blood, it is de facto control that must be considered, i.e., whether control of the two corporations is in fact exercised by the same group.

H.A. Fawcett & Son, Ltd. v. The Queen, 80 DTC 6195, [1980] CTC 293 (FCA)

A legatee of a control bloc of shares obtained control of the company immediately upon the death of the testator, notwithstanding that the will was not probated until after the end of the company's taxation year, because title to the shares vested in him immediately upon the death by force of the will, and his right to vote the shares was not dependent upon those shares being registered. It was irrelevant that notice requirements precluded him from being able to compel a shareholders' meeting to be held before the end of the taxation year. The company accordingly was associated with other companies that were controlled by him.

International Iron & Metal Co. Ltd. v. MNR, 72 DTC 6205, [1972] CTC 242, [1974] S.C.R. 898, aff'g 69 DTC 5445, [1969] CTC 668 (Ex Ct)

A corporation ("Burland") was owned by nine children of four fathers. The taxpayer ("International Iron") would have been indirectly controlled by the same children through their respective four holding companies but for the possible effect of an agreement among the four holding companies and the four fathers which provided that so long as the fathers were alive, they would be designated and elected as directors of the four holding companies, and the affirmative vote of a majority of those directors would be required for the effecting or validating of any acts of the four holding companies. In the Exchequer Court, Gibson J., in finding that International Iron and Burland were controlled by the same group of persons for purposes of s. 39(4) of the pre-1972 Act, stated (p. 5448):

"The fact that a shareholder in such a corporation may be bound under contract to vote in a particular way regarding the election of Directors (as in this case), is irrelevant to the said meaning of 'control' because the corporation has nothing to do with such a restriction."

In affirming this finding, Hall J. in the Supreme Court stated (p. 6207):

"The meaning of 'control' in s. 39(4)(b) ... means the right of control that is vested in the owners of such a number of shares in a corporation so as to give them the majority of the voting power in the corporation."

MNR v. Consolidated Holding Co. Ltd., 72 DTC 6007, [1972] CTC 18, [1974] S.C.R. 419

Two individuals (Harold Gavin and Robert Gavin) each owned 50% of the shares of one corporation ("Consolidated") which in turn owned 43.7% of the voting shares of a second corporation ("Martin"). 45.9% of the voting shares of Martin were held by an estate of which the three executors were Harold, Robert and the Montreal Trust Company. Under the terms of the will of the deceased, the shares of Martin could be voted by a majority of the executors. Judson J. stated (p. 6008):

"Here, if one looks at the facts as a whole, one finds that the two Gavins, by combining, controlled the vote of the estate shares. They already controlled the voting of 'Consolidated'. In this case, therefore, both corporations are controlled by the same group of persons, namely, the two Gavins."

Consolidated and Martin accordingly were held to be associated by virtue of s. 39(4)(b) of the pre-1972 Act.

Vina-Rug (Canada) Ltd. v. MNR, 68 DTC 5021, [1968] CTC 1, [1968] S.C.R. 193

Because John Stradwick, Jr., his brother W.L. Stradwick and H.D. McGilvery, who collectively owned more than 50% of the shares of Stradwick's and Vina-Rug, had at all material times a sufficient interconnection as to be in a position to exercise control over the two corporations, and therefore constituted a 'group of persons' within the meaning of s. 39(4) of the pre-1972 Act, the two corporations were associated. It was irrelevant whether other combinations of majority shareholders could be found.

Vineland Quarries and Crushed Stone Ltd. v. MNR, 66 DTC 5092, [1966] CTC 69 (Ex Ct), briefly aff'd 67 DTC 5283 (SCC)

In finding that under the above arrangement, Vineland and S. & T. "were controlled by the same ... group of persons" (i.e., Saunder and Thornborrow) for purposes of s. 39(4)(b) of the pre-1972 Act, Cattanach J. stated (p. 5098):

"In my view the word 'controlled' in section 39(4)(b) contemplates and includes such a relationship as, in fact, brings about a control by virtue of majority voting power, no matter how that result is effected, that is, either directly or indirectly."

Yardley Plastics of Canada Ltd. v. MNR, 66 DTC 5183, [1966] CTC 215 (Ex Ct)

Two corporations whose voting shares were held as follows

| Shareholder | Canadian Moldings | Yardley Plastics |

| Hill | 4.6% | 28% |

| Hill III | 18.6% | 22.5% |

| Wycoff | 21.7% | 11% |

| Daymond | 21.7% | 14% |

| Strachan | 21.7% | nil |

| Ebner | nil | 17% |

| Jacobson | 11.7% | 7.5% |

| 100% | 100% |

were found to be controlled by the same group of persons, namely, Hill, his son, Hill III, and three unrelated individuals, namely, Wycoff, Daymond and Jacobson, following the assumption to this effect by the Minister. Although Noël J. rejected a submission of the Minister "that the latter is allowed to choose out of several possible groups any aggregation holding more than 50% of the voting power ... and that such a group then becomes irrebuttably deemed to be the controlling group for purposes of section 39(4) of the [pre-1972] Act as this could lead to an absurd situation where no two large corporations in this country would be safe from being held to be associated" (p. 5188), he went on to indicate that the question whether there is control by a "group of persons" owning a majority of the voting power is a question of fact and, here, the taxpayer had failed to challenge the Minister's assumption of fact (and apparently would have had difficulty doing so in light of the common management of the two corporations). With respect to a submission that Hill and Hill III were a related group which were deemed by s. 139(5d) (now s. 251(5)(a)) to control Yardley Plastics, and that this related group did not control Canadian Moldings, the two corporations could therefore not be held to be associated, Noël J. held that s. 139(5d), although extending the concept of a related group, could not restrict the meeting of s. 39(4)(b) of the pre-1972 Act (subsequently, s. 256(1)(b) of the Act).

See Also

Quincaillerie Brassard Inc. v. MNR, 91 DTC 559 (TCC)

A corporation ("Fercomat") was found to be controlled by the same group of persons as each of two other corporations ("Quincaillerie" and "Ferronnex") notwithstanding a submission that Fercomat was controlled by one individual alone who owned 44.9% of its voting shares but held a power of attorney (which he exercised) over shares of his children representing a further 39.6% of the votes of Fercomat. Tremblay TCJ. also applied the proposition that (p. 564):

"[W]here several groups could possibly have legal control, the one which has de facto control must be chosen, that is, the one which sets company policy that must be implemented by the board of directors."

Express Cable Television Ltd. v. MNR, 82 DTC 1431 (TRB)

A partnership of corporations (variously referred to as "Welsh Antenna" and "Antenna Systems") held a majority of the shares of one corporation ("Victoria") but not of the taxpayer. In finding that Victoria and the taxpayer were both controlled by a group of persons consisting of Welsh Antenna and a former employee of Welsh Antenna who, through a corporation owned by him held shares in both Victoria and the taxpayer, Mr. Cardin stated (at p. 1437) that "the existence of voting trusts, comunity of interest and other common links between the shareholders [is] pertinent in determining which of the majority groups does in fact control two corporations" and found that there was such community of interest between Welsh Antenna and its former employee (notwithstanding that no voting agreement existed) as they were both involved in the business of the taxpayer and Victoria (television production) and they both provided business services to the taxpayer and Victoria (managerial services, in the case of Welsh Antenna, and sales services in the case of the former employee).

King George Hotels Ltd. v. MNR, 68 DTC 635 (TAB)

The taxpayer, which was indirectly controlled by children of the Leier family, was found to be associated with the corporation ("J.P.") that was owned by an incorporated charitable foundation whose trustees were two members of the Leier family and a legal advisor, and with the corporation (Joseph Enterprises) that was owned equally by Mrs. Leier and the foundation.

Buckerfield's Ltd. v. MNR, 64 D.T.C 5301 (Ex Ct)

Two companies that were vigorous competitors (Pioneer and Federal) each owned one-half of the shares of two other companies (Buckerfield's and Green Valley). In finding that Buckerfield's and Green Valley were associated corporations pursuant to s. 39(4)(b) of the pre-1972 Act by virtue of their control by the same group of persons, Jackett P. stated (at p. 5303):

Many approaches might conceivably be adopted in applying the word "control" in a statute such as the Income Tax Act to a corporation. It might, for example, refer to control by "management", where management and the board of directors are separate, or it might refer to control by the board of directors. ... The word "control" might conceivably refer to de facto control by one or more shareholders whether or not they hold a majority of shares. I am of the view, however, that in Section 39 of the Income Tax Act [the former section dealing with associated companies], the word "controlled" contemplates the right of control that rests in ownership of such a number of shares as carries with it the right to a majority of the votes in the election of the board of directors.

Jackett P. further stated (at pp. 5303-5304) that "the word 'group' in its ordinary meaning ... can refer to any number of persons from two to infinity".

Administrative Policy

5 April 1995 T.I. 5-941474

S.256(7)(b) will apply where the same group of unrelated individuals controls an amalgamated corporation as controlled both the predecessors.

80 C.R. - Q.25

A person who is the registered and beneficial owner of the shares of one company is the "same person" for purposes of s. 256(1)(b) where he also holds the shares of another company as trustee or executor.

IT-64R3 "Corporations

Association and Control - after 1988".

Paragraph 256(1)(c)

Cases

1056 Enterprises Ltd. v. The Queen, 89 DTC 5287 (FCTD)

The Minister assessed the taxpayer, whose shares were owned 99% by an individual ("John"), on the basis that John's brother ("William"), who was virtually the sole shareholder of another corporation ("Northland"), also had a 50% interest in the taxpayer. Muldoon J. found that although the brothers had an initial oral agreement to this effect, "it ceased before the brothers could carry it into effect", with the result that the taxpayer and Northland were not associated (p. 5293).

See Also

Disher-Winslow Products Ltd. v. MNR, 52 DTC 27 (TAB)

An individual (Edward) was the holder and beneficial owner of substantially all the shares of the taxpayer and his father (Clarence) was the holder and beneficial owner of a substantial portion of the voting shares of a second corporation ("DeWalt"). In addition, Clarence held one share of the taxpayer on behalf of Edward, and Edward held one share of DeWalt on behalf of Clarence. In finding that Edward and Clarence did not "own" shares of both corporations for purposes of s. 36(4)(b)(iii) of the Act as it then read, Mr. Fordham stated (at p. 28):

"In Stroud's Judicial Dictionary, 2nd Edition Ed., p. 1387, it is stated that the owner of a property is the person in whom (with his or her consent) it is for the time being beneficially vested, and who has the occupation, or control, or usufruct of it. In my view, Clarence ... did not have such an interest in the share of the appellant's stock registered in his name and the real owner was Edward ... ."

Paragraph 256(1)(d)

Cases

Allied Farm Equipment Ltd. v. MNR, 73 DTC 5036, [1972] CTC 619 (FCA)

Each of three brothers owned and controlled one Canadian corporation and, among the three of them, owned and controlled a U.S. corporation. In finding that the U.S. corporation was associated with each Canadian corporation (with the result that each Canadian corporation was associated with the other two Canadian corporations under the pre-1972 version of s. 256(2)), Jackett C.J. noted (p. 5037) that the rules in s. 39(4) of the pre-1972 Act applied "for the purposes of this section", that those rules determined the amount of tax payable under Part I by associated corporations and that it followed "that section 39(4) has no application to determine whether two corporations are associated unless they are both subject to income tax under Part I of the Income Tax Act".

1056 Enterprises Ltd. v. The Queen, 89 DTC 5287 (FCTD)

An individual ("John") was issued 99% of the shares of the appellant ("Cantex") on its incorporation, even though John's brother had provided Cantex with $20,000 in cash and a corporation controlled by the brother ("Northland") had financed the purchase by Cantex of certain equipment on the preliminary verbal understanding (made prior to its incorporation) that when Northland was repaid, John's brother would receive 49% of Cantex's shares. Since no agreement or legal relationship along these lines ever was consumated, Cantex was not associated with Northland.

Holiday Luggage Mfg. Co. Inc. v. The Queen, 86 DTC 6601, [1987] 1 CTC 23 (FCTD)

Father and son each owned substantially all the shares of a CCPC, and 30% of the shares of a U.S. corporation. Joyal, J. held that the two CCPC's were not associated because foreign corporations were intended to be excluded from the category of corporations for the purposes of that section. The definition of "corporation" in s. 248(1) was not conclusive.

Administrative Policy

4 April 1990 T.I. (September 1990 Access Letter, ¶1439)

Where A is the sole shareholder of A Ltd., and A along with his three brothers are the four trustees, having equal powers, of a testamentary trust holding all the shares of C Ltd., then A Ltd. and C Ltd. will not be associated. The 25% ownership test requires the person to have a beneficial interest in the shares.

IT-64R3 "Corporations: Association and Control - after 1988".

Paragraph 256(1)(e)

Cases

The Queen v. B.B. Fast & Sons Distributors, 86 DTC 6106, [1986] 1 CTC 299 (FCA)

William Fast and his wife each owned 50% of the shares of one corporation ("Willmar"), and William Fast and his 4 siblings each owned 20% of the shares of the taxpayer. The requirement that a related group own a 10% interest in each corporation was interpreted as requiring that two (or more) members of that related group hold a 10% aggregate interest in each corporation. Since Mrs. Fast owned none of the taxpayer's shares, this requirement was not satisfied. "William Fast, the only common relative in each group, could not by himself be a 'group'".

Atomic Truck Cartage Ltd. v. The Queen, [1985] 2 CTC 21 (FCTD)

The common shares of three corporations were held by individuals, all of whom were related to each other, as follows:

| Entreprises: | X - 49.5%; | A - 49.5%; | B - 1% |

| Atomic: | X - 42%; | Y - 42%; | C - 16% |

| Roclar: | D - 49%; | Y - 49%; | E - 2% |

Since no two individuals held, as a group, 10% or more of the shares of two corporations, and since the holdings of a member of such a group of two persons was irrelevant, the three corporations were not associated.

The Queen v. Mars Finance Inc., 80 DTC 6207, [1980] CTC 216 (FCTD)

Where the conditions of S.256(1)(e) are met, then it is irrelevant that de facto control of one of the corporations is exercised contrary to the wishes of a distinct group which controls the other corporation.

Administrative Policy

86 C.R. - Q.18 B.B. Fast.

IT-64R3 "Corporations: Association and Control - after 1988".

Subsection 256(1.1)

Administrative Policy

20 February 1996 T.I. 960508 (C.T.O. "Stock Dividend Shares those of a Specified Class?")

Where a share has been issued as a stock dividend, the consideration for which the share was issued would be considered to be nil.

31 October 1991 T.I. (Tax Window, No. 12, p. 13, ¶1560)

The "amount of unpaid dividends" referred to in s. 256(1.1)(e) may include accumulated but unpaid dividends.

3 September 1991 T.I. (Tax Window, No. 8, p. 3, ¶1437)

A share with no entitlement to dividends generally will comply with s. 256(1.1)(c).

If the share terms provide that the shares will become voting under certain circumstances, the test in paragraph (b) will not have been met from the time of issuance of the share.

Subsection 256(1.2) - Control, etc.

Cases

9044-2807 Québec Inc. v. The Queen, 2004 DTC 6636, 2004 FCA 23

Noël J.A. indicated (at p. 6639) that in order to avoid any conflict between applying the results of the de jure control and de facto control:

"The Act now provides in subparagraph 256(1.2)(b)(ii) that a corporation may be controlled by a person notwithstanding that the corporation is also controlled or deemed to be controlled by another person. Accordingly, Transport Couture could exercise de facto over MR1 and MR2 although de jure lay elsewhere."

Administrative Policy

89 C.R. - Q.14

Where a minor child owns 10% of the common shares of Holdco which owns 100% of the common shares of Opco, s. 256(1.2)(e) will not be applied more than once in respect of the shares of Opco held by Holdco (i.e., once when the parent is deemed to own the shares of Holdco by virtue of s. 256(1.3) and once in respect of the child's actual ownership of Holdco shares). Therefore, the parent would be deemed to own 10% of the shares of Holdco and 10% of the share of Opco.

88 C.R. - Q.39

RC will identify any group of persons, related or unrelated, without considering whether any group acts in concert.

Paragraph 256(1.2)(a)

Administrative Policy

IT-64R3 "Corporations: Association and Control - after 1988".

Paragraph 256(1.2)(b)

Administrative Policy

18 October 89 Meeting with Quebec Accountants, Q.3 (April 90 Access Letter, ¶1166)

Where A owns 95% of the shares of Corporation A and the other 5% are owned by B, and B owns all the shares of Corporation B, and to fund a particular project, Corporation B issues shares to A who then owns 10% of its issued shares, Corporations A and B would be deemed to be controlled by a group (A and B) regardless of the small participation of each individual in their corporations and regardless whether or not A and B have a mutual interest.

IT-64R3 "Corporations: Association and Control - after 1988".

Paragraph 256(1.2)(c)

See Also

Kruger Wayagamack Inc. v. The Queen, 2015 TCC 90

51% and 49% of the taxpayer's shares (being common shares) were held by a business corporation ("Kruger") and a Government of Quebec corporation ("SGF").

Jorré J found that Kruger's shareholding had a fair market value of over 50% of that of all the shares, so that ss. 256(1.2)(c) and 256(1)(a) applied to deem the taxpayer to be associated with Kruger, stating (at para. 118):

Given the effect of paragraph 256(1.2)(g)… what one has to value is Kruger's holding of 51% of the shares with some expected financial return per share and SGF's holding of 49% of the shares with the same expected financial return per share in circumstances where it is as if a third party ran the appellant without Kruger or SGF having the slightest influence on that third party. In such circumstances, it is hard to imagine why someone would pay a different price per share whether they bought 49 shares, 51 shares or all 100 shares.

A unanimous shareholder agreement gave SGF the right, on its 9th anniversary, to require Kruger to purchase all of its shares for their FMV, determined without minority discount or marketability discount, provided that credit agreement covenants were met. Jorré J accepted that such a right might increase the value of SGF's shares relative to Kruger's. However, since the benefit of this put right could not be assigned to a third-party purchaser of SGF's shares, it did not affect the shares' FMV.

See summary under s. 256(1)(a).

Administrative Policy

29 June 1995 T.I. 951064 (C.T.O. "Cotrustees of Different Trusts Same Persons")

"Where the co-trustees of two trusts are the same persons and one of the trusts owns shares representing more than 50% of the fair market value of all of the issued and outstanding shares of one corporation (Corporation A) and the other trust owns shares representing more than 50% of the fair market value of all of the issued and outstanding shares of a second corporation (Corporation B), we believe that Corporation A and B would be associated by virtue of paragraph 256(1.2)(c), unless the conditions described in subsection 256(4) of the Act are satisfied."

Paragraph 256(1.2)(d)

Administrative Policy

IT-64R3 "Corporations: Association and Control - after 1988".

Paragraph 256(1.2)(f)

Cases

The Queen v. Propep Inc., 2010 DTC 5088 [at 6882], 2009 FCA 274

The taxpayer was owned by another corporation (9059) which, in turn, was owned by a Quebec trust whose first-ranking beneficiary was 9059, and second-ranking beneficiary was the son of an individual who controlled two other corporations with which CRA had found the taxpayer was associated. It was accepted that the taxpayer would be so associated if the son was deemed by s. 256(1.2)(f)(ii) to own 9059.

Although the discretion conferred on the trustees to distribute capital to the son could not be exercised before the winding-up of 9059 or the expiration of 100 years, the trustees could in exercising their discretion and at the time of their choosing wind up 9059, thereby making the son the sole beneficiary. Accordingly, the son was deemed by s. 256(1.2)(f)(ii) to own 9059. In addition, he was an income beneficiary, and under the Act an income beneficiary was treated as a beneficiary of the trust. Finally, he was a beneficiary under the expanded definition of "beneficially interested" in s. 248(25). In this regard, Noël JA stated (at paras. 23-24) after referring to s. 248(25)(a):

The TCC judge seems to be of the opinion that this definition does not apply here because the expression "beneficially interested" is not used in either of the provisions dealing with associated corporations (256(1)( c ), 256(1.2) and 256(1.3))... . With respect, the expression "beneficially interested" does not have to be reproduced in each provision where it is likely to be applied. This concept applies each time the question arises whether a person is "beneficially interested" in a particular trust. A person who has a contingent right to the capital or income of a trust is "beneficially interested" for the purposes of the Act.

Administrative Policy

IT-64R3 "Corporations: Association and Control - after 1988".

Subsection 256(1.3) - Parent deemed to own shares

Administrative Policy

13 October 2000 T.I. 2000-003891 -

With respect to a situation where father held, as the sole trustee of a discretionary trust for minor children, 24% of the shares of a corporation, the Agency indicated that ss.256(1.2)(f)(ii) and 256(1.3) would not be double-counted so as to result in father being deemed to own 48% of the shares.

4 March 1994 T.I. 932874 (C.T.O. "Associated Corporations")

Where 16% of the shares of a corporation are held by a discretionary family trust and three beneficiaries of the trust (being siblings) are under the age of 18, the application of s. 256(1.3) will not result in the parent being deemed to own 48% of the shares. Instead, the application of ss.256(1.2)(f)(ii) and 256(1.3) will be considered from the viewpoint of each of the beneficiaries, on a person-by-person basis, with the result that the shares of the corporation will not be double counted.

21 August 1992 T.I. 921988 (April 1993 Access Letter, p. 155, ¶C248-133)

Where Mr. A. owns all the shares of X Ltd. and Mrs. A, who owned all the shares of Y Ltd., freezes her interest in Y Ltd. in favour of a discretionary trust for her children who are under 18 years of age, X Ltd. and Y Ltd. will be associated corporations.

Subsection 256(1.4) - Options and rights

Administrative Policy

16 March 2011 T.I. 2010-0380571E5 -

The wording of ss. 251(5)(b)(ii) and 256(1.4)(b) is sufficiently broad to cover a situation where a person does not have control over the triggering event giving him or her the right to cause the corporation to redeem, acquire, or cancel shares in its capital stock held by another person. CRA has ruled that these provisions would not generally apply where a corporation is required to redeem or purchase for cancellation shares held by a shareholder who has been found guilty of fraud in relation to the corporation (see 2002-0172315 and 2006-0167361E5).

24 July 1998 T.I. 980787

Where a corporation and its two 50% shareholders have agreed that the shares held by the shareholder shall be purchased by the corporation in the event that the shareholder ceases to be an employee, s. 256(1.4)(b) may apply in circumstances where the particular shareholder is in a position to trigger the event so as to force the corporation to acquire shares owned by the other shareholder.

18 June 1998 T.I. 980570

In indicating that s. 256(1.4)(b) could apply where pursuant to a unanimous shareholders agreement a corporation would automatically acquire the shares of a shareholder where there is a change in control of the shareholder, a receiver of the shareholder was appointed, the shareholder breached specified covenants in the agreement, the shareholder encumbered its shares or they were attached, Revenue Canada stated

"... The wording in subsection 256(1.4)... will not be applied unless both (or all) parties clearly have either a right or an obligation to buy or sell as the case may be. In a situation where a unanimous shareholders agreement provides for an automatic acquisition or redemption of shares of a corporation by the corporation upon the occurrence of a specified triggering event, it is our view that the corporation clearly has an obligation to acquire and the shareholder clearly has an obligation to sell the shares upon the occurrence of the specified triggering event. Consequently, paragraph 256(1.4)(b) will apply when a person or partnership is in a position to cause the occurrence of a specified triggering event referred to in such a unanimous shareholders agreement."

5 February 1993 T.I. (Tax Window, No. 28, p. 3, ¶2411)

S.256(1.4)(a) applies in a situation where the articles of incorporation or a shareholders' agreement for a corporation having three equal common shareholders (one of whom also owns all the preferred shares) provides that in the event a shareholders' meeting is called to consider a reorganization of the share capital, a winding-up of the corporation, or an amendment to the share provisions of the preferred shares, the preferred shares will be given the right to vote, with the result that the preferred shareholder would hold more than 50% of the votes.

S.256(1.4)(a) also would apply where it was provided that if any shareholder failed for a period of greater than one year to attend shareholders' meetings, the remaining shareholders would have the option to acquire the shares of the absent shareholder.

91 C.R. - Q.11

Where parties to a shareholders' agreement have made a bona fide attempt to define "permanent disability", their definition will be given weight by RC.

20 April 1990 T.I. (September 1990 Access Letter, ¶1440)

Permanent disability refers to impairments that are expected to last for continuous periods that will exceed the period provided in s. 118.4(1)(a).

In a situation where no one shareholder alone controls the corporation, the fact that a particular board of directors may cause a corporation to redeem its shares does not in itself cause s. 256(1.4)(b) to apply. If a shareholders' agreement were to provide that should a shareholding employee ceased to be employed by the corporation his shares will automatically be acquired by the corporation, no one would appear to have a right to cause the corporation to acquire the employee's shares.

IT-64R3 "Corporations: Association and Control - after 1988".

Subsection 256(2) - Corporations associated through a third corporation

Administrative Policy

10 December 1993 T.I. 5-933554 -

Re RC's requirements for acceptance of a late-filed Form T2144.

16 June 1993 T.I. (Tax Window, No. 32, p. 12, ¶2607)

An election by a corporation under s. 256(2) will not affect the status of the other two corporations in question for purposes of ss.129(6) and 181.5(7).

6 September 1991 T.I. (Tax Window, No. 9, p. 6, ¶1447)

Example of the application of s. 256(2).

30 March 1990 Memorandum (August 1990 Access Letter, ¶1395)

The phrase "either of the other two corporations" refers to both corporations. In the situation where corporations B, C, D and E are each associated with A but are not otherwise associated with each other, a single election by A listing B, C, D and E will be sufficient to disassociate the five corporations in a particular taxation year for the purposes of s. 125.

2 November 89 T.I. (April 90 Access Letter, ¶1181)

An election made by a corporation under s. 256(2) not to be associated is valid only for the purposes of section 125 and not for purposes of the deeming rule in s. 129(6)(b).

88 C.R. - F.Q.40

The election by the third corporation should be filed with its return of income for the relevant taxation year.

Subsection 256(2.1) - Anti-avoidance

Cases

Les installations de l'Est Inc. v. The Queen, 91 DTC 5185 (FCTD)

It was found that a second corporation was incorporated in order to deal with difficulties the first corporation had been having with its sub-contractors and in order to permit the son of the principal shareholder of the first corporation to develop his business career in managing the second corporation.

Maritime Forwarding Ltd v. The Queen, 88 DTC 6114, [1988] 1 CTC 186 (FCTD)

The taxpayer was unsuccessful in his assertions that the main reasons for the separate existence of a company (controlled by a family trust) whose principal activity was the leasing of trucks to a company ("MFL") controlled by the taxpayer and in the forwarding agent business were strictly to reduce truck leasing costs, protect his capital investment in MFL by removing tangible assets from possible seizures and benefiting his children.

Kencar Enterprises Ltd. v. The Queen, 87 DTC 5450, [1987] 2 CTC 246 (FCTD)

The taxpayer was formed for income tax estate planning reasons, and the taxpayer's appeal accordingly failed.

Alpha Forming Corp. Ltd. v. The Queen, 83 DTC 5021, [1982] CTC 425 (FCTD)

A direction was made under old S.247(2) respecting 2 corporations the first one of which ("Alpha") was owned primarily by 2 individuals, and the second of which ("Jenmari") was owned by their wives. Although it was accepted that Jenmari was incorporated for reasons entirely unrelated to tax advantage and that it continued to exist primarily for those reasons (i.e., to provide a vehicle for placing ownership of real property in the hands of their wives), there was an income-splitting purpose in the following transaction sufficient to violate the test in old S.247(3)(b)(ii): the rental of a crane by Jenmari to Alpha, with a consequent transfer of significant income in the form of rental charges from Alpha to Jenmari.

The Queen v. Covertite Ltd., 81 DTC 5363, [1981] CTC 464 (FCTD)

The onus under the section was not met by an unsubstantiated explanation by the wife of the chief shareholder of the first company that the second company was set up in Ontario to permit her to flee the social climate that prevailed in Quebec in the early 1970's and to invest in Ontario.

Honeywood Ltd. v. The Queen, 81 DTC 5066, [1981] CTC 38 (FCTD)

Since no "positive evidence" was adduced by the Crown to prove that one of the main reasons for the companies' separate existence was the reduction of income taxes otherwise payable, the taxpayer companies through adducing oral evidence had discharged the onus of proof placed on them by old S.7(3)(b)(ii).

Lenco Fibre Canada Corp. v. The Queen, 79 DTC 5292, [1979] CTC 374 (FCTD)

The wife of the owner of two companies incorporated the plaintiff company, which hired her as its sole employee, in order for the plaintiff company to act as an agent in the purchasing and selling of synthetic fibres or synthetic waste materials for her husband's companies. It was found that the main reason for having the plaintiff exist to engage in the purchasing and selling of fibres (rather than having those activities performed by the wife as an employee of her husband's companies), was to insulate her commission earnings from any claims against her husband's companies, and that none of the main reasons for the separate existence of the plaintiff was the reduction of taxes.

Decker Contracting Ltd. v. The Queen, 79 DTC 5001, [1979] CTC 838 (FCA)

It was argued that the separate existence of a company ("Garyray") owned by the wives of the individual owners of the appellant, did not result in a reduction of the tax burden of the appellant because if the appellant had not paid Garyray to effect repairs to its equipment it would have made deductible payments to third parties in order to have the repair work done. It was found, however, that although repairs prior to the incorporation of Garyray may have been carried out by third parties, the reference in old s. 247(3)(b)(ii) to "taxes that would otherwise be payable" "must refer to the tax which would have been payable had the Appellant ... employed its own mechanics and owned its own premises".

Debruth Investments Ltd. v. M.N.R., 75 DTC 5012, [1975] CTC 55 (FCA)

A successful businessman who carried on a real estate business through a company ("Don River") owned by him and his wife set up four separate trusts for his children which then incorporated four companies with nominal capital. Don River entered into a real estate partnership with the four companies. Everything was "carried on precisely as before except income split four ways found its way into the accounts of these four new separate companies." The reduction of income taxation was one of the main reasons for having separate companies for the four trusts.

First Pioneer Petroleums Ltd. v. MNR, 74 DTC 6109, [1974] CTC 108 (FCTD)

"[T]he question of fact to be determined is not whether the tax advantage is the main reason but rather whether it is a main reason for the separate existence of the corporations during the particular period in question. I have already indicated that I believe it was a main reason in this instance."

See Also

Maintenance Euréka Ltée v. The Queen, 2011 DTC 1319 [at 1812], 2011 TCC 307

Hogen J. found that the taxpayers' reassessment under s. 256(2.1) was justified, given that (para. 15):

The evidence shows that the two corporate appellants use the same staff to meet their administrative service needs. Each bears half the expenses, salaries and other administrative costs. They share the premises where they are each headquartered, though each signed a lease under which they paid a separate rent for the premises in question. In addition, both had the same phone and fax number during the period in issue.

He went on to state (at para. 25):

[T]axpayers' appeals tend to succeed when they provide evidence that, on a balance of probabilities, the reason for the existence of the two corporations is asset protection, activity diversification, decentralization for greater profit, a spouse's intent to operate his or her own business, or estate planning, to cite some examples.

Taber Solids Control (1998) Ltd. v. The Queen, 2009 DTC 1899, 2009 TCC 527

Before going on to find that the taxpayer and a corporation owned by the wife of the majority shareholder of the taxpayer, were associated because of the de facto control of the other corporation by the taxpayer and its majority shareholder, C. Miller, J. first found that the two corporations were not deemed to be associated under s. 256(2.1) since the decision to separate business operations between the two corporations was made in order to protect valuable assets from possible law suits arising from operations (para. 17).

LJP Sales Agency Inc. v. The Queen, 2004 DTC 2007, 2003 TCC 851

The reason for the separate existence of two corporations, one of them owned by the husband, and the other one substantially owned by his wife, was to accommodate their desire to equally split their future accrual of wealth, so that they could each leave their estates as they wished (in the context of a vehement disagreement as to whether any property should be left to their children). The two corporations were not associated.

Saratoga Building Corp. v. MNR, 93 DTC 564 (TCC)

A finding was made that none of the main reasons for the separate incorporation of the taxpayers involved tax savings given that they had been separately incorporated primarily for the purpose of market targeting, and that their separate existence also enhanced financing opportunities and the protection of family assets from certain financial risks.

Administrative Policy

2013 Ruling 2013-0498961R3 - Partner creating a professional corporation

CRA accepted a representation that the professional corporations (ProCorps) whose respective employees and controlling shareholder was a partner of a professional partnership and which provided professional services to the partnership at a fee were not partners of each other, including representations that each ProCorp is free to compete with the partnership. CRA accordingly ruled that the ProCorps are not required to share the small business deduction under the specified partnership income rules.

CRA went on to provide an opinion:

that the incorporation of ProCorps to provide the Professional Services to the Partnership will not, in and of itself, cause subsection 256(2.1)...to be applicable to the ProCorps.

84 C.R. - Q.87

Listing of RC criteria re the "most effective manner" phrase appearing in old s. 247(2)(a).

Subsection 256(3) - Saving provision

Administrative Policy

IT-64R3 "Corporations: Association and Control - after 1988".

Subsection 256(5.1) - Control in fact

Cases

Plomberie O.C. Langlois Inc. v. The Queen, 2007 DTC 5662, 2006 FCA 113

In rejecting a submission on behalf of the taxpayer that the Tax Court judge had ignored the terms of a unanimous shareholder agreement in finding that an individual, who held 50% of the shares of the taxpayer, had de facto control of the taxpayer, the Court noted that the parties did not comply with the shareholders agreement and also noted that such individual had caused the corporation to engage in numerous unusual transactions without shareholder approval.

9044-2807 Québec Inc. v. The Queen, 2004 DTC 6636, 2004 FCA 23

The trial judge had correctly found that a corporation ("ML1") whose shares were owned by an individual ("father"), and a corporation ("ML2") 90% of whose shares were owned by his wife ("mother") were subject to de facto control of a corporation ("Transport Couture") owned by the five sons of father and mother, so that ML1 and ML2 were associated with Transport Couture. ML1 and ML2 were economically dependent on Transport Couture (they would not have been in a position to pursue their activities if their contracts with Transport Couture had been terminated by it), Transport Couture exercised operational control (the sons and the manager of Transport Couture took all important decisions, the involvement of the father (who had Alzheimer's disease) was nil and that of mother was limited to one information session a month), and the relationship of trust which father and mother had with their sons caused them to rely on Transport Couture and delegate all decision-making powers they held as shareholders.

In commenting on the test in s. 256(5.1) Noël J.A. stated (at p. 6640) that:

"Whatever factors are considered, they must show that a person or group of persons has the clear right and ability to change the board of directors of the corporation in question or to influence in a very direct way the shareholders who would otherwise have the ability to elect the board of directors ... in other words, the evidence must show that the decision-making power of the corporation in fact lies elsewhere than with those who have de jure control."

Lanester Sales Ltd. v. The Queen, 2003 DTC 997 (TCC), aff'd 2004 DTC 6461, 2004 FCA 217

Arrangements pursuant to a shareholders agreement under which the franchisor of the taxpayer (which owned 49.9% of the taxpayer's shares) was entitled to nominate one of the two directors to the board of directors, and arrangements for pooling the funds collected by the taxpayer with other franchisees in collectively managed bank accounts did not cause the taxpayer to be controlled by the franchisor. Furthermore, these arrangements were part of the extremely broad range of contractual and financial arrangements between franchisors and franchisees contemplated by s. 256(5.1). It was not necessary to deal with the suggestion of counsel for the Crown that the phrase "dealing at arm's length" should be interpreted as implicitly being qualified by the word "otherwise" although Bowman A.C.J. was inclined to agree with this interpretation.

Silicon Graphics Ltd. v. The Queen, 2002 DTC 7113, 2002 FCA 260

The taxpayer was found to be a Canadian-controlled private corporation, as neither de jure nor de facto control was held by non-residents.

Respecting a submission of the Crown that a U.S. corporation ("Silicon U.S."), that had lent U.S $5 million to the taxpayer and made financial contributions for software development and marketing, whose founder was a director of the taxpayer and whose hardware was utilized by the taxpayer's software, exercised de facto control over the taxpayer. Sexton J.A. stated (at p. 7121) "that in order for there to be a finding of de facto control a person or group of persons must have the clear right and ability to effect a significant change in the board of directors or to influence in a very direct way the shareholders who would otherwise have the ability to elect the board of directors." Here, Silicon U.S. was merely protecting its interests as lender to the taxpayer, and Toronto management managed the taxpayer and annually prepared the slate of individuals to be elected to the board.

See Also

Kruger Wayagamack Inc. v. The Queen, 2015 TCC 90

Kruger Inc. was the 51% shareholder of the taxpayer and was entitled under the unanimous shareholders agreement between it and the other shareholder (SGF) to appoint three of the five directors. However, Jorré J found that such a wide range of decisions were specified in the USA to require unanimous director (or shareholder) approval – to the point that he characterized Kruger as having control of only operating, and not strategic, decisions – that Kruger did not have de jure control.

In considering whether Kruger had de facto control, reference also could be made to non-USA agreements, namely, for the provision by Kruger of management services, and the marketing by it of the taxpayer's products, including the sale of wood pulp to Kruger itself, as well as to Kruger's specialized industry knowledge. However, these were not enough to establish de facto control, given significant built-in restrictions in those agreements and given the significant role of SGF.

See summary under s. 256(1)(a).

Solutions Mindready R&D Inc. v. The Queen, 2015 CCI 17

All of the shares of the taxpayer were held by a trust whose two trustees were also directors of a public company and the sole directors of the subsidiaries of the public company which were beneficiaries of the trust. Those two trustees managed the taxpayer by virtue of a unanimous shareholder agreement. The taxpayer was formed to carry on SR&D which previously had been carried on by the public company pursuant to a contact with it.

In concluding that the taxpayer was not a Canadian-controlled private corporation (and therefore not entitled to enhanced SR&D investment tax credits) as it was subject to the de facto control of the public company, as described in s. 256(5.1), Favreau J stated (at para.35, TaxInterpretations translation) that

it is now well established that the determination of the required influence for a corporation to be considered as being controlled by another requires an examination of the operational and economic decisions of the corporation in question. A decisive economic role permitting a corporation to be in a position to impose its will on the management of the affairs of another corporation is sufficient to constitute control in fact.

and found that the public company had both substantial operational influence (e.g., management in common, sharing of workplace and employees, preparation of accounts by the same firm, and payment of the taxpayers' employees only as it was paid by the public company) and economic influence (e.g., it co-signed a loan, the taxpayer's research projects were determined by it, and the taxpayer's royalties were minimal compared to its required funding.)

McGillivray Restaurant Ltd. v. The Queen, 2015 DTC 1030 [at 134], 2014 TCC 357

The taxpayer's business was a franchised restaurant. Boyle J found that it was required to share the small business deduction with corporations controlled de jure by the husband ("Robert") of its 76% shareholder on the basis that Robert had de facto control of it as described in s. 256(5.1): Robert as officer and director made all the important decisions; it was dependent on one of his companies for the provision of administrative services as well as for the leasing to it of the premises; and she could not have sold her controlling interest without the consent of the franchisor.

After referring to the Silicon Graphics statements that, to have de facto control of a corporation, a person or persons must have the clear ability to effect a significant change in the board or directly influence the shareholders, Boyle J stated (para. 44) that more recently it had been found to be appropriate to rely on "who controlled day‑to‑day operations, who made all the decisions, who signed all the business agreements, invoices and cheques, and who was in a position to exert economic pressure in order to have its will prevail with respect to the business and… the corporation," and then stated (at paras. 46-7):

[T]he issue appears to have been very clearly addressed and settled by the Federal Court of Appeal… . I will therefore be considering such broader manners of influence in applying the Silicon Graphics meaning of de facto control to the particular facts of this case. …[I]n…applying the de facto control test…this Court should be attempting to determine who is, in fact, in effective control of the affairs and fortunes of the corporation.

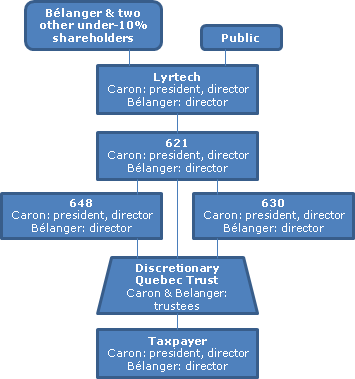

Lyrtech v. The Queen, 2013 DTC 1147 [at 820], 2013 TCC 12, aff'd 2014 CAF 267

In order to generate refundable investment tax credits for research and development expenditures, a Canadian public corporation ("Lyrtech") transferred its R&D operations (but not its intellectual property rights) to the taxpayer, which was intended to qualify as a Canadian-controlled private corporation. The taxpayer initially was financed through debt owing to a discretionary trust which also held it shares. The trust's trustees were two individuals, one of whom was the president and a director of Lyrtech, of the other trust beneficiaries and of the taxpayer, and the other of whom was a director of such companies and a co-founder of Lyrtech. The trust's capital beneficiaries were various subsidiaries of Lyrtech. Lyrtech agreed to pay 10% of any related product sales or 25% of any related royalties to the taxpayer. The taxpayer entered into a unanimous shareholders' agreement with the trustees.

After accepting (at para. 18) that control as defined in s. 256(5.1) encompassed both de jure control and de facto control (so that the presence of de jure control by A did not preclude de facto control by B) [confirmed by Scott JA in the FCA at para. 38] and finding (at para. 25) that the trustees (whose decisions required unanimity under the declaration of trust) together had de jure control of the taxpayer, Favreau J. went on to find that Lyrtech had de facto control of the taxpayer, as described in s. 256(5.1), so that the taxpayer did not qualify as a CCPC. Among other factual considerations were that:

- the two individuals controlling the taxpayer de jure also were the key directors and officers of Lyrtech (which had a seven-person board) and of other group companies, and they were not independent directors of Lyrtech;

- the taxpayer had virtually no revenues, was under-capitalized, and depended on Lyrtech to finance its activities either directly or through guarantees; and

- Lyrtech determined what R&D work the taxpayer would conduct.

Taber Solids Control (1998) Ltd. v. The Queen, 2009 DTC 1899, 2009 TCC 527

The taxpayer ("Taber 1998") and its majority shareholder ("Ken") were found to have de facto control over a corporation that was owned by Ken's wife ("Old Taber") given that the taxpayer was the sole customer of Old Taber and Ken's wife did not have the contacts or appropriate business acumen to carry out the business of Old Taber without her husband's assistance and decision making. Before reaching this conclusion, C. Miller, J. stated (at para. 25) that "the appropriate question is whether Ken or Taber 1998 had direct or indirect influence over Old Taber's board decision making".

Brownco Inc. v. The Queen, 2008 DTC 2591, 2008 TCC 58

The taxpayer was subject to the de facto control of the holder of ½ of its shares ("Bost") given that under the unanimous shareholder agreement between BOST and the other 50% shareholder (the "USA"), the board was to consist of one director nominated by each shareholder, a nominee of Bost was to be the Chairman, and in the event of a tie of votes, the Chairman was entitled to cast the deciding vote. The franchise exception in s. 2056(5.1) did not apply as the USA was not similar to a franchise agreement (it did not deal with providing the trade name used by Bost to the taxpayer, it did not contain any clauses dealing with the granting of a licence or a lease of property or a distribution or supply of any product, it did not specify how tasks were to be accomplished or how the business of the taxpayer was to be conducted, and instead dealt with matters between the two shareholders) and the fact that the taxpayer and Bost were not dealing at arm's-length was evidenced by the fact that the taxpayer provided a guarantee of Bost liabilities without receiving anything in return.

Corpor-Air Inc. v. The Queen, 2007 DTC 841, 2006 TCC 75

The taxpayer was found to be subject to the de facto control of the husband of the individual who was its sole director, shareholder and officer given that the companies that were virtually its only source of revenue (in the form of management fees) were controlled by her husband, the taxpayer did not own any capital assets (other than non-interest bearing advances owing to it by that group of companies), its only capital was non-interest bearing advances that had been made to it by that group of companies and inferences to be drawn from the unsatisfactory nature of her testimony and the failure to call her husband as a witness.

Avotus Corp. v. The Queen, 2007 DTC 215, 2006 TCC 505

A non-resident shareholder of the taxpayer, who owned one-half of the taxpayer's shares and, by virtue of being chairman, was entitled pursuant to the by-laws to have the casting vote in the event of a tie vote, thereby had control of the corporation within the extended meaning of s. 256(5.1) and also had de jure control by virtue of such rights. Paris J. stated (para. 70) that "the legal effect of a casting vote provision in the by-laws would not be negated by Malone's alleged ignorance of the provision".

Plomberie J.C. Langlois Inc. v. The Queen, 2006 DTC 2997, 2004 TCC 734, aff'd supra.

The taxpayer and its 50% corporate shareholder were found to be subject to the de facto control of the same person (an individual who was the sole shareholder of the 50% shareholder) given that that individual was the sole director and the president of the taxpayer. Lamarre Proulx J. stated (at paras. 38-39):

"The decision-making role belongs to the director of a corporation, and it is the one that is associated with the notion of control in fact of a corporation."

Cornu, dir., Vocabulaire juridique, 2d ed. (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1990) defines the word "[control]" in a manner that I find interesting, at p. 207:

[TRANSLATION]

- 3 Dominion over the management of a business or organization; power ensuring the one who has it a dominant influence in the direction of a group, a corporation, etc., or the orientation of its future.

L.D.G. 2000 Inc. v. The Queen, 2003 DTC 827, Docket: 1999-2309-IT-G (TCC)

50% of the shares of the taxpayer were acquired by another corporation ("Gestion") following which the two individual shareholders of the taxpayer holding the remaining 50% of the shares continued to make the day-to-day decisions respecting the taxpayer's affairs.

Angers T.C.J. found that Gestion through a wholly-owned subsidiary of Gestion ("Bermex") exercised control over the taxpayer as described in s. 256(5.1). Following the acquisition of the taxpayer by Gestion, the taxpayer became economically dependent on Bermex (its sales increased approximately ten-fold with between 79% and 95% of its sales being to Bermex, and Bermex provided the financing necessary for the taxpayer's operations). Decisions concerning sales and purchases were made by Gestion and the taxpayer was permitted to adjust its billing to Bermex at the end of each fiscal year so as to ensure that it would receive a profit set at 15% of its sales to Bermex.

Transport M.L. Couture Inc. v. The Queen, 2003 DTC 817, Docket: 2000-2264-IT-G (TCC), aff'd sub. nom. 9044-2807 supra.

The taxpayer was found to be controlled within the meaning of s. 256(5.1) by another corporation ("Transport Couture") given the economic dependence of the taxpayer on Transport Couture and the operational control of Transport Couture (the taxpayer had no employees, all management and other personnel services were provided to it by Transport Couture and Transport Couture was its only customer) and given that Transport Couture was owned indirectly by the five sons of the sole shareholder of the taxpayer, who was in declining health and who relied on his sons.

Miller Estate v. The Queen, 2002 DTC 1228, Docket: 1999-2987-IT-G (TCC)

An order of the District Court of Ontario that there be no administration or distribution of an estate pending a decision of the widow of the deceased as to whether she wanted to proceed with the election under s. 5(2) of the Family Law Act (Ontario) to take under the will neither deprived the estate of control of three corporations that had been controlled by the deceased nor gave it to her. She had a rather limited right to veto some of the acts of administration or distribution but she could not elect directors nor could she influence the way in which the directors went about running the day-to-day affairs of the three corporations. Accordingly, the estate controlled directly or indirectly in any manner whatever the corporations for purposes of former s. 85(4).

Mimetix Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. The Queen, 2001 DTC 1026, Docket: 1999-4847-IT-G (TCC), briefly aff'd 2003 DTC, 2003 FCA 106

Fifty percent of the voting shares of the taxpayer together with most of its capital (in the form of preferred shares and an interest-free loan) was held by a non-resident corporation ("Mimetix"), which sublicensed to the taxpayer the non-exclusive right to conduct in Canada clinical trials and other investigations involving the taxpayer's principal product.

Although two of the three directors of the taxpayer and its president were individuals who were not employees of Mimetix, Mimetex was found to have the control of the taxpayer contemplated in s. 256(5.1) given that: the only individuals who actually exercised control and supervision over the taxpayer were an individual ("Eaton") who was the Chief Executive Officer of Mimetex and a director of the taxpayer, and another individual (who was the President of Mimetex) who had been appointed as a signing officer of the taxpayer by Eaton without consulting the Canadian directors; and the Canadian directors (one of whom nominally was the President of the taxpayer) had very little knowledge about important particulars of the affairs of the taxpayer and did not make any decisions concerning its operations.

Multiview Inc. v. The Queen, 97 DTC 1489 (TCC)

Brulé TCJ. applied the criteria in Interpretation Bulletin IT-64R3, para. 17, 19 to find that the taxpayer was not subject to the de facto control of a non-resident individual.

Rolka v. MNR, 62 DTC 1394, [1962] CTC 637 (Ex Ct)

An individual was found to indirectly control a corporation ("Nelmar") whose "shareholders were merely his nominees, prepared at all times to carry out his wishes and instructions (and, in fact, did so) and exercised no independent judgment or sought to get the best possible terms for Nelmar."

Administrative Policy

11 October 2013 APFF Roundtable Q. , 2013-0495811C6 F

S. 188 of the Quebec Business Corporations Act provided that "Unless otherwise provided in the by-laws, in the case of a tie, the chair of the meeting casts the tie-breaking vote." Where the shares of a corporation are held equally by two shareholders and s. 188 applies, does the chair have de facto control of the corporation under s. 256(5.1)?

CRA stated (TaxInterpretations translation):

[W]e do not believe that BCA section 188, respecting the conduct of an annual shareholders meeting, automatically confers de facto control of a corporation on the person occupying the post of chair of the meeting and having a casting vote. In this regard, we note that BCA section 186 provides that "Unless otherwise provided in the by-laws, the president of the corporation chairs a shareholders meeting," and that the chair, in general, is elected by the directors of the corporation.

[D]e facto

control…remains a question of fact… .For example, we note that in Brownco Inc. v. The Queen, 2008 DTC 2591 (TCC) and Avotus Corp. v. The Queen, 2007 DTC 215 (TCC), the Court recognized that the right to a casting vote attaching to the position of chair of the board of directors or of the shareholders' meeting accorded, to a shareholder holding 50% of the voting shares of a corporation, an influence whose exercise would result in de facto control of the corporation.

11 October 2013 APFF Roundtable Q. , 2013-0493651C6 F

All the voting common shares of Opco (carrying on an active business) are held by a discretionary inter vivos trust which was settled by the uncle of the four beneficiaries (the "children"), and its non-voting retractable preferred shares (which were issued on an estate freeze and have a value approximating 50% of the value of Opco) are held by a spousal testamentary trust, of which the four children are the beneficiaries upon the death of the surviving spouse (i.e., their mother), and of which their father was the testator).

If the testamentary trust redeemed its preferred shares for a note, would it be affiliated with Opco following such retraction?

It would be a question of fact as to whether the holding of the debt by the testamentary trust resulted in de facto control of Opco (as described in s. 256(5.1)). In such event, the exception in s. 40(3.61) would not prevent the application of the stop-loss rule in s. 40(3.6) "given that the testamentary trust is not an estate." CRA also noted [TaxInterpretations translation] that although IT-64R4 indicates that the holding of a large debt is relevant to determining whether the holder has de facto control of the debtor:

This factor nonetheless was considered of little importance in Technical Interpretation XXX where the debt represented virtually all the net value of a corporation but all its assets consisted of readily marketable securities which could serve to repay the debt held by an estate without imperiling its investment operations.

23 June 1995 T.I. 951047

With respect to a situation where one corporation ("Supplyco") owned 50% of the shares of another corporation ("Distributorco") and the majority of the products sold by Distributorco were acquired from Supplyco, RC stated that "a franchise or similar agreement which provides one party, such as Supplyco, a measure of control over the business carried on by another corporation, such as Distributorco, would not in itself result in Supplyco having control over Distributorco provided that the parties otherwise deal at arm's length and the purpose test referred to therein is satisfied. However, in a situation where such control over the business carried on by Distributorco is combined with item (d) in paragraph 19 of IT-64R3, being economic dependence on Supplyco as its single supplier, it is our view that Supplyco would have de facto control ... ."

20 March 1995 T.I. 942429

With respect to whether an incorporated professional business would be subject to de facto control by a professional body where an order has been issued by the body as a result of disciplinary action or where a quasi-professional has not achieved a certain level of expertise in his professional field, RC commented that the reference to "other similar agreement or arrangement" referred to an agreement or arrangement that was motivated by business relationships rather than some other factor.

1 September 1994 T.I. 5-950392

A submission that a 60% non-resident shareholder did not control what was alleged to be a CCPC by virtue of terms of the shareholders' agreement that required various decisions to be made with the consent of at least 61% of the shareholder votes was rejected on the basis that the non-resident had de jure control. RC effectively indicated that the defined phrase included de jure control.

28 July 1994 T.I. 941745

"In addition to the factors expressed in paragraph 19 of IT-64R3, the Department would also consider the composition of the board of directors, the control of day-to-day management and operation of the business and the ownership of a large debt of the corporation in the determination of whether any influences exist. In the case of related persons, the Department has stated that it would look at a person's ability to demonstrate their economic independence and autonomy in determining whether there exists significant influence over a family member who is a shareholder of the corporation. Where a shareholder has no source of income and relies on the income of a related person, we may conclude that the related person providing the financial support may have influence over that shareholder ... ."

91 C.R. - Q.9

Provided that Canadian-resident trustees, in fact, control a private corporation, it would be a CCPC even if it has non-resident beneficiaries.

A.P.F.F. 1990 Round Table, Question 36, No. 9317770

In order for the exception to apply, the arrangement must have been entered into for commercial and not for the purpose of controlling the other party. A franchisor is permitted to contractually impose restrictions respecting the financing or payment of dividends of the franchisee if such restrictions were imposed for protecting its investment and not for the purpose of controlling the franchisee.

20 March 1995 T.I. 942429 (C.T.O. "256(5.1) Control and Governing Bodies")

With respect to the situation where an incorporated professional is required to carry on business under the supervision and control of an unrelated third party, for example, because of an order issued by a governing body following disciplinary action being taken, RC observed that the expression "or other similar agreement or arrangement" should be interpreted as referring only to agreements and arrangements of the same general nature enunciated, i.e., those that are motivated by business relationships which the parties share. It was also noted that the "similar agreement or arrangement" need not be evidenced in writing.

12 August 1992 T.I. 921604 (April 1993 Access Letter, p. 155, ¶C248-134; Tax Window, No. 23, p. 12, ¶2130)

Where a shareholder's agreement between two 50% shareholders provides that each shareholder will elect two members of the board of the directors and that one director elected by the first shareholder will be the chairman of the board and will have a casting vote, that first shareholder will have the de facto control described in s. 256(5.1).

29 July 1992 Memorandum (Tax Window, No. 21, p. 4, ¶2037)

Where the chair of a shareholder's meeting has the deciding vote and is one of two 50% shareholders, she generally will have de facto control of the corporation.

29 July 1992 Memorandum (Tax Window, No. 21, p. 1, ¶2038)

An estate that does not own voting shares of a corporation nonetheless may be in a position to exercise some influence over the corporation that would result in it having de facto control of the corporation, for example, if it holds a demand promissory note and calling the note would have an adverse impact on the corporation's operations.

29 June 1992 Memorandum 7-920444 -

Discussion of whether persons have effective control with respect to a substantial block of shares in a widely-held corporation where there is effective control over the composition of the board of directors.

91 C.R. - Q.12

Where a 50% shareholder has a casting vote by virtue of being chairperson, the corporation generally will be controlled directly or indirectly in any manner whatever by that person.

20 September 1990 Memorandum 7-902376 -

"The introduction of subsection 256(5.1) expands the judicially based de jure control concept to include de facto control situations where the expression 'controlled directly or indirectly in any manner whatever' is used. In other words, that expression refers to both de jure and de facto control whereas the words 'control' or 'controlled' refers to the judicially adopted de jure control only unless a specific provision defines control for a specific purpose such as subsection 186(2)."

3 January 1990 T.I. 5-9256 (Tax Window Files "'Meaning of Canadian-Controlled Private Corporation' - Control Test"

Where a Canadian-resident private corporation owns all the shares of a resident Canadian corporation ("N") which, in turn, owns all the shares of a Canadian corporation ("A"), A will not qualify as a Canadian-controlled private corporation because of the direct de jure control by N. The introduction of the concept of de facto control by the enactment of s. 256(5.1) did not eliminate the relevance of direct de jure control by a non-resident person.

22 September 89 T.I. (February 1990 Access Letter, ¶1130)

Father has his corporation invest $150,000 in a corporation owned by his daughter and her husband, by acquiring shares that were retractable at any time that is three years after their issue. The retractability of the shares gave father's corporation influence that, if exercised, would result in the daughter's corporation being controlled by father's corporation at the particular time.

89 C.R. - Q.15

"While the ability to elect a majority of the directors, or to control the day to day management and operation of the business, may be indications of such influence, there are other factors such as the ownership of a large debt of the corporation, which might also indicate such influence."

3 Aug. 89 T.I. (Jan. 90 Access Letter, ¶1086)

RC rejected a submission that "control in fact" means control by a person who does not otherwise control the corporation where that person has any direct or indirect influence that, if exercised, would give that person the ability to cast or cause to be cast, in such manner as that person may determine, the majority of votes in the election of the board.

88 C.R. - Q.41

The enactment of ss.256(5.1) and 256(1.4) did not alter RC's policy described in IT-64R2, paragraph 31 respecting rights of first refusal and shotgun arrangements.

Gouin-Toussaint, September 1989 Revenue Canada Round Table (Dec. 89 Access Letter, ¶1040)