Cases

Canada Life Insurance Co. of Canada v. A.G of Canada, 2015 ONSC 281

In order that the applicant ("CLICC") could realize an accrued capital loss on its 99% limited partner interest in a subsidiary limited partnership ("MAM LP") (and following preliminary dividends):

- On December 7, 2007, MAM LP distributed an asset to CLICC and a wholly-owned subsidiary of CLICC ("CLICC GP") based on their respective 99% and 1% interests.

- On December 31, 2007, the interests of CLICC and CLICC GP in MAM LP were cancelled and MAM LP distributed all its remaining property (other than $100 of limited partner capital) pro rata to CLICC and CLICC GP.

- One hour later, MAM LP was dissolved and immediately thereafter, the remaining $100 of partnership capital was distributed pro rata to CLICC and CLICC GP.

- At 11:59 p.m., CLICC GP was wound up and its assets and liabilities acquired and assumed by CLICC.

- CLICC GP was formally dissolved on October 14, 2008.

After CRA assessed to deny the loss claimed by CLICC on the basis that the s. 98(5) rollover applied, the applicant applied for the transactions in 2 to 4 to be rectified so that s. 98(5) could not apply (entailing a distribution on December 31 of some of the partnership property to both CLICC and CLICC GP, a transfer of CLICC's LP interest to CLICC GP, a resulting wind-up of MAM LP into CLICC GP also on December 31, 2007 and the wind-up of CLICC GP into CLICC on April 30, 2008 (i.e., more than 3 months after December 31.)

In granting the requested relief, Pattillo J noted (at para. 39) that "at all material times, CLICC and the other parties…had a continuing specific intention…to create a tax loss…of approximately $168 million" and (at para. 38) that the Attorney General's ("AG's") arguments that rectification was restricted to correcting mistakes in the instruments used to implement a definite and ascertainable tax plan had been rejected in Fairmont.

In response to an AG argument that the proposed rectification transactions contained two more transactions than had occurred in December 2007, CLICC had applied after the hearing of the motion to propose alternative rectification transactions whose only change from the original transactions was to defer the winding-up of CLICC GP from December 31, 2007 to April 30, 2008. As the originally requested rectification relief was granted, this amendment motion was dismissed.

Telus Communications Inc. v. A.G. of Canada, 2015 ONSC 6245

The Telus group had a tiered partnership structure. Its management decided that Telus would make a multi-tier alignment election under s. 249.1(9) so that two subsidiary partnerships ("TCC" and "TMC"), which were believed to be in a qualifying multi-tiered partnership structure would each have a January 31 fiscal period end. 15 months after filing the election on a timely basis, they discovered that a minority interest of TCC in a third partnership ("EnStream") had been overlooked (and not disclosed in the election or in a previous ruling application to CRA), which meant that the election was invalid as EnStream had a different fiscal period end than TCC and TMC.

In granting the applicants' application to correct this error by allowing a retroactive transfer of TCC's interest in EnStream to a wholly-owned corporate subsidiary of TCC (which Telus submitted it would have done at the time if it had remembered the minority interest), and after noting the Crown submission (at par. 17) that "the Applicants are asking the Court to retroactively declare that new transactions…took place when they did not," Hainey J stated (at para. 17):

The Applicants had a specific and continuing intention throughout to file a valid Election. They are not attempting to retroactively avoid an unintended tax disadvantage.

He stated (at para. 20) that in the alternative, and following TCR, he would "rely on the equitable jurisdiction of this court to relieve the Applicants from the effect of their mistake."

Zhang v. The Queen, 2015 BCSC 1256

The taxpayer (Mr. Zhang) briefly sought advice from his tax accountant (Bob) as to how he could extract funds from his Chinese operating company ("LABest"), and was advised that exempt surplus dividends could be paid to Canada if the shares were held by a Canadian holding company. Mr. Zhang incorporated a B.C. company ("Beamtech") and secured approval from a Chinese authority for the transfer of his shares of LABest to Beamtech for cash consideration of U.S.$150,000 – which was effected without further specific advice from Bob.

When CRA assessed Mr. Zhang under s. 69 on the basis that the fair market value of the shares was Cdn.$661,164, so that the transfer had generated a capital gain, Beamtech issued 1,000 common shares to Mr. Zhang as purported additional consideration for the transfer, a joint s. 85(1) election was filed and a rectification order was sought to have the share issue be considered to have occurred on the date of the transfer.

In dismissing the petition, Butler J stated (at para. 39):

To use the language of the Ontario Court of Appeal in Juliar, here, the true agreement between the parties was the acquisition of Mr. Zhang's interest in LABest by Beamtech in a manner that would allow for the distribution of LABest's income in British Columbia on a basis which attracted the minimum amount of income tax. It was not based on Beamtech acquiring the interest in LABest in a manner which would not attract immediate liability for capital gains tax. That was a secondary concern and one which Mr. Zhang asked Bob not to investigate. He did not seek assistance regarding the capital gains issue until long after the transaction concluded… .

Fairmont Hotels Inc. v. A.G. Canada, 2015 ONCA 441, aff'g 2014 ONSC 7302, leave granted, SCC docket 36606

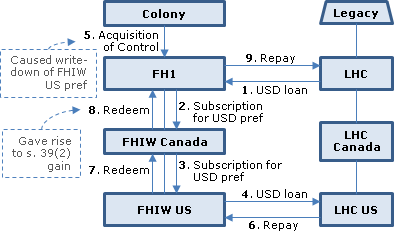

In order to facilitate the acquisition in 2002 of a hotel in Washington by a REIT ("Legacy") of which it was the manager, Fairmont Hotels Inc. ("FHI") borrowed U.S.$67.6 million from a subsidiary of Legacy ("LHC"), subscribed for U.S.$67.6 million of U.S. dollar denominated preference shares of a Canadian subsidiary of FHI ("FHIW Canada"), which subscribed for U.S.$67.6 million of U.S. dollar denominated preference shares of a U.S subsidiary of FHIW Canada ("FHIW US"), which lent U.S.$67.6 million to an indirect U.S. subsidiary of LHC ("LHC US"). As a result of an acquisition of control of FHI in 2006, an accrued FX loss on the preferred shares of FHIW US held by FHIW Canada was extinguished under s. 111(4)(d), so that FHIW Canada was no longer hedged from a Canadian tax standpoint. The Fairmont advisors were aware of this but deferred dealing with this issue to another day.

In 2007, FHI was approached on an urgent basis by Legacy to unwind the above "reciprocal loan arrangement" in connection with an imminent sale of the Washington hotel. In the rush of the moment, the FHI VP of Taxation forgot that FHIW Canada was unhedged, and the structure was unwound through inter alia a redemption of the preference shares of FHIW Canada held by FHI, so that FHIW Canada realized an FX gain under s. 39(2). This mistake was not discovered until a subsequent CRA audit. Essentially the same reciprocal loan structure and mistaken unwinding strategy was used in connection with a Seattle hotel of Legacy.

Simmons JA noted (at para. 5) that, in granting an application to rectify the 2007 unwinding transactions so that the U.S. dollars advanced by FHIW Canada to FHI were a loan rather than redemption proceeds, Newbould J had found that from 2002 on there had been a continuing Fairmont intention for the reciprocal loan arrangement "to be carried out on a tax…neutral basis through a plan whereby any foreign exchange gains wold be offset by corresponding foreign exchange losses" and that "the preferred shares of the two relevant companies…would not be redeemed."

In dismissing the crown's appeal, Simmons JA stated (at paras. 10, 12):

Juliar … does not require that the party seeking rectification must have determined the precise mechanics or means by which the party's settled intention to achieve a specific tax outcome would be realized. Juliar holds, in effect, that the critical requirement for rectification is proof of a continuing specific intention to undertake a transaction or transactions on a particular tax basis.

…[I]t was unnecessary that the respondent prove that it had determined to use a specific transactional device - loans - to achieve the intended tax result. That the respondent mistakenly failed to employ an appropriate transactional device to achieve the intended tax result does not alter the nature of the respondent's settled tax plan: tax neutrality in its dealings with Legacy and no redemptions of the preference shares in question.

Harvest Operations Corp v. A.G. (Canada), 2015 ABQB 327

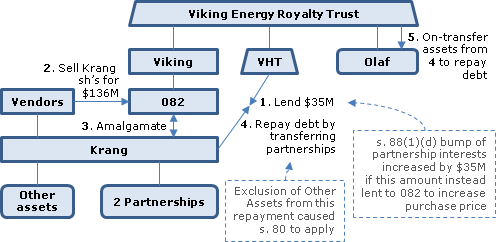

The Bump Mistake

A predecessor in interest of the applicant ("Viking") entered a multi-step acquisition and restructuring transaction to acquire an arm's length corporation ("Krang"). The plan was originally for a sibling unit trust of the taxpayer ("VHT") to lend $35 million to the taxpayer's subsidiary ("082"), which would then acquire all the shares of Krang for $171 million, with 082 and Krang then amalgamating to form "Krang #2".

On the day of closing, a Krang creditor unexpectedly required Krang to repay its revolving credit facilities rather than consenting to the transaction. Consequently, VHT lent the $35 million directly to Krang, thereby reducing the purchase price paid by 082 for the Krang shares by $35 million. This had the effect of reducing the s. 88(1)(d) "bump" of the cost to Krang #2 of partnership interests previously held by Krang by the same amount, thereby resulting in a taxable capital gain on a subsequent transfer of those interests described below.

The taxpayer applied to have the transaction rectified to reflect that the loan was made to 082 instead of Krang, and that those funds were used to subscribe for additional shares of Krang.

Dario J dismissed the taxpayer's application, stating (at paras. 77, 81 and 82):

[T]his is not a case of the parties "wrote it down wrong", but rather the parties got it wrong.

… To the extent we are talking only about the increased bump room due to the Krang Debt, the evidence does not establish that the inability to benefit from this tax treatment would have terminated the acquisition, or that the common intent of the parties that drove them to the formation of the transaction was frustrated.

… The intent to complete a transaction in the most tax efficient manner possible is not sufficiently specific. The Applicant must establish how the parties had intended on achieving this tax objective… .

Cases, such as Fairmont, where courts granted "rectification where there was no ‘particular way' the parties had intended to achieve the tax objective… run contrary to the express views of the Supreme Court of Canada as set out in Performance Industries and others…" (paras. 46, 49).

Here, the taxpayer's tax advisor had listed a number of possible options to deal with the last-minute hurdles in a tax-efficient manner - none of them were taken, and furthermore none of them matched the order being sought.

The Other Assets Mistake

A subsequent leg of the series involved transferring Krang's assets (now Krang #2's assets) to VHT in purported full repayment of debt owing, with VHT then transferring the same assets to a subsidiary partnership ("Olaf"), also as a purported full debt repayment. Approximately $12 million of the $170 million in assets of Krang #2 were not transferred, with the result that both debts had been settled without full repayment, so that the debt forgiveness rules applied to both Krang #2 and VHT.

After concluding that rectification was not available in any event, Dario J stated (at para. 92):

In the present case, where these assets were unknown or forgotten, not specifically referred to in the Step Memorandum, remained (and presumably, with respect to prepaid expenses and depreciable assets, used) in the Krang #2 entity, and subsequently recorded in Krang #2's tax filings (including recording a capital cost allowance on the assets), the Applicant has not met the requisite burden of proof to establish intent.

Mac's Convenience Stores Inc. v. A.G. of Canada, 2015 QCCA 837

The appellant, which was a wholly-owned Ontario subsidiary of a Quebec corporation ("CTI"), paid a $136 million dividend to CTI in connection with a "Quebec shuffle" transaction. The tax advisor did not focus on the resulting reduction in the appellant's retained earnings which, under the s. 18(4) thin cap rule, caused a substantial portion of the interest on a $185 million loan owing to a related non-resident corporation to become non-deductible.

In finding that the appellant could not retroactively rectify the dividend so as to be a stated capital distribution instead, and after noting (at para. 34) that AES and Riopel dealt with related parties committing an error in giving effect to a "legitimate corporate transaction for the purpose of avoiding, deferring or minimizing tax" and correcting "that error to achieve the tax consequences originally and specifically intended and agreed upon," Schrager JA stated (at para. 43):

The payment of the 136 million dollar dividend to CTI was intended and was effected. … Reduction of capital was not intended. The unintended consequences of the dividend, by ricochet, resulted from the thin capitalization rules and was not part and parcel of the transaction. … There was no common intention of the parties regarding these rules as they were never contemplated and so cannot be the object of a meeting of the minds to which a court can give effect.

A.G. Canada v. Le Groupe Jean Coutu (PJC) Inc., 2015 QCCA 838, leave granted, SCC docket 36505

The professional advisors of the respondent ("PJC Canada") recommended two alternatives ("Scenarios 1 and 2") for it to neutralize the effect of foreign exchange fluctuations on the value of its investment in its wholly-owned U.S. subsidiary ("PJC USA"). Under the alternative chosen (Scenario 1), PJC Canada lent U.S.$120 million to PJC USA, and PJC USA used U.S.$70 million in share subscription proceeds received by it from PJC Canada to make a loan of U.S.$70 million to PJC Canada. CRA assessed on the basis that the interest on the loan by PJC USA to PJC Canada gave rise to foreign accrual property income ("FAPI") to PJC Canada. PJC Canada and PJC USA then sought to rectify on the basis of having Scenario 2 (under which the FAPI would have been reduced to nil by interest expense) implemented retroactively.

In reversing the finding below that rectification was available, Schrager JA quoted (at para. 32) the statement in Graymar that "rectification is available in order to avoid a tax disadvantage which the parties had originally transacted to avoid, it is not available to avoid an unintended tax disadvantage which the parties had not anticipated," stated (at para. 38) that a "general intent…that their transaction be ‘tax neutral' is not sufficiently determinate" and further stated (at paras. 37, 38):

The parties…achieved their intended purpose of neutralizing the effect of the exchange fluctuations. …They are taxed on that basis even though they did not foresee the [FAPI] tax consequences.

Kaleidescape Inc. v. MNR, 2014 ONSC 4983

The applicant ("K-Can") was intended to qualify as a Canadian-controlled private corporation. Its outstanding shares consisted of 100 Class A non-voting common shares and 100 Class B voting common shares held by a Delaware corporation ("K-US"), and 100 Class C special voting shares held by a trust for K-Can employees whose trustee was a trust company (Computershare) and whose named settlor was K-Can. A unanimous shareholders' agreement ("USA") conferred the powers of the directors on the K-Can shareholders. The Declaration of Trust provided:

5.2 ...Upon the direction of the Settlor, the Trustee shall...exercise any voting rights...

5.9 Where this Deed of Trust requires or authorizes the Settlor to give directions to the Trustee, the Trustee shall accept only a direction in writing from the CEO or President of the Settlor.

CRA concluded that these two provisions gave the non-resident CEO of K-Can the authority to direct Computershare how to vote the Class C shares of K-Can, so that K-US had de jure control of K-Can.

K-Can and Computershare then signed a Deed of Rectification, amending the Deed of Trust, which recited that paragraph 5.9 might "be misinterpreted as that the CEO or the President…has the power to change …the Board of Directors," and amended it to provide that the Trustee shall accept only a direction in writing "in the form of a certified copy of a resolution from the Board of Directors of the Settlor." The amendment was stated to be effective from the date of settlement of the trust subject to approval of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice (and otherwise was effective on the date of the amendment).

The Crown argued inter alia that the amendment would have no effect on the de jure control of K-Can: due to the USA, the Board of K-Can had no right to instruct the Trustee and, as the Trustee was unwilling to vote without instruction, K-US controlled the Class C shares.

In granting the requested rectification order to retroactively confirm the amendment, Carole Brown J stated (at paras. 28-30) that she was satisfied that "the intention throughout was to ensure that K-Can…qualified for CCPC status and for the tax credits available," "that the wording chosen was chosen by mistake and not to intentionally give K-US de jure control over K-Can," and (respecting the above argument) "the Deed makes it clear that the decision-making body is the Board of Directors."

Canada (Attorney-General) v. Brogan Family Trust, 2014 ONSC 6354

The respondent family trust obtained a rectification order, to permit trust distributions to minor grandchildren beneficiaries, on 26 November 2010, which was shortly after a sale of a business by the trust. The gains on the sale were allocated to the beneficiaries for the 2010 year. The Crown did not become aware of the rectification until a subsequent CRA audit, and CRA brought a motion 10 months after this discovry to set aside the rectification order on the ground that it ought to have been given notice.

In dismissing this motion, Ray J stated (at para. 13):

I am not persuaded that… CCRA [sic] was affected by the order of McLean, J. … [After citing Canada v. Simard-Beaudry Inc. [1971] F.C. 396, para. 20:] I don't accept the CCRA's contention that tax liability was established at the moment of the sale with the amount of the tax to be determined after the return was filed by the respondents. To accept the CCRA's argument would in principle implicate the CCRA as tax collector in virtually every proceeding in the courts involving damages for termination of employment, personal injury income loss claims, family matters, or for the purchase and sale of a business.

The respondent's situation therefore was distinguishable from the situation where an applicant had already been reassessed by CRA (Aim Funds Management Inc. v. Aim Trimark Corporate Class Inc. [2009] O.J. 2408) or where the rectification application had been triggered by an adverse CRA ruling (Snow White Productions Inc. v. PMP Entertainment Inc, 2004 BCSC 604).

Furthermore, CRA had not (as required by the Rules) brought its motion "forthwith," which:

has been interpreted to mean "without unreasonable delay considering the object of the rule and the circumstances of the case" [citing Coopers & Lybrand Ltd. v. Richter & Associates, [2000] OJ No. 2073 (Ont SC) aff'd [2001] OJ No. 1087 (Ont CA)].

Fairmont Hotels Inc. v. A.G. Canada, 2014 ONSC 7302, aff'd supra

In order to facilitate the acquisition in 2002 of a hotel in Washington by a REIT ("Legacy") of which it was the manager, Fairmont Hotels Inc. ("FHI") borrowed U.S.$67.6 million from a subsidiary of Legacy ("LHC"), subscribed for U.S.$67.6 million of U.S. dollar denominated preference shares of a Canadian subsidiary of FHI ("FHIW Canada"), which subscribed for U.S.$67.6 million of U.S. dollar denominated preference shares of a U.S subsidiary of FHIW Canada ("FHIW US"), which lent U.S.$67.6 million to an indirect U.S. subsidiary of LHC ("LHC US"). As a result of an acquisition of control of FHI in 2006, an accrued FX loss on the preferred shares of FHIW US held by FHIW Canada was extinguished under s. 111(4)(d), so that FHIW Canada was no longer hedged from a Canadian tax standpoint. The Fairmont advisors were aware of this but deferred dealing with this issue to another day.

In 2007, FHI was approached on an urgent basis by Legacy to unwind the above "reciprocal loan arrangement" in connection with an imminent sale of the Washington hotel. In the rush of the moment, the FHI VP of Taxation forgot that FHIW Canada was unhedged, and the structure was unwound through inter alia a redemption of the preference shares of FHIW Canada held by FHI, so that FHIW Canada realized an FX gain under s. 39(2). This mistake was not discovered until a subsequent CRA audit.

In granting an application to rectify the 2007 unwinding transactions so that the U.S. dollars advanced by FHIW Canada to FHI were a loan rather than redemption proceeds (and in responding to the Attorney General's position (at para. 21) "that a loan to FHI…was not part of the plan in 2006 or even 2007"), Newbould J found that from 2002 on there had been a continuing Fairmont intention for the reciprocal loan arrangement to be tax neutral (although "they had no specific plan as to how they would" "deal with the unhedged position of FHIW Canada" following the 2006 acquisition of control" (para. 33)), that "the purpose of the 2007 unwind of the loans was not to redeem the preference shares of FHIW Canada or FHIS Canada, but to unwind the loans on a tax free basis," and that "the redemption of the preference shares was mistakenly chosen as the means to do so" (para. 43). As he was bound by Juliar, he did not have the "luxury" of following Graymar and, in any event, he did not think that Brown J in that case "has accurately described what happened in Juliar" (para. 41).

Essentially the same reciprocal loan structure and mistaken unwinding strategy was used in connection with a Seattle hotel of Legacy, and addressed by Newbould J in the same manner.

Jaft Corporation v. Canada (AG), 2014 DTC 5080 [at 7056], 2014 MBQB 59

CRA had found that the applicant's research into solutions for Sick Building Syndrome based on air treatment qualified for scientific research and experimental development credits. In proceeding to develop related products, the applicant employed several individuals on terms that their compensation be based "solely on the work done that meets the requirements of SR&ED." The applicant applied the presumed SR&ED credits towards payroll remittances. CRA found that the work did not qualify, and the taxpayer applied to have the employment contracts rescinded or declared void ab initio.

After finding that allowing the application would needlessly interfere with the Tax Court's jurisdiction on this matter (see summary under s. 171(1)), McKelvey J decided in the alternative to disallow rescission. While the applicant relied on Stone's Jewellery and Juliar, the facts were closer to Bramco. She stated (at para. 44):

This case smacks of attempts to adopt a retroactive/no-risk tax planning scenario or, in essence, rewriting history. The payroll tax remittances are lawfully owed ... and should not be rectified, rescinded, or declared void ab initio.

Re: Pallen Trust, 2014 DTC 5039 [at 6726], 2014 BCSC 305

An individual ("Pallen") or his spouse ("Tonn") settled the taxpayer, a family discretionary trust, and transferred his shares of "New Integrated" to a personal holding company ("Pallen Holdings") in exchange for shares under s. 85(1). Pallen Holdings then subscribed $100 for (discretionary dividend) Class D shares of New Integrated, and sold them to the taxpayer for the same amount, which was their fair market value. New Integrated then paid approximately $1.75M in dividends on the Class D shares to the taxpayer, as to which $1.74M was satisfied by issuing a promissory note. Over a year later, New Integrated paid $0.25M to partially repay the promissory note.

The plan was intended to result in s. 75(2) attributing the $1.75M in taxpayer dividend income to Pallen Holdings, which was a beneficiary of the taxpayer, so that such dividends would be received tax-free under s. 112(1). However, following Sommerer, CRA (which viewed the plan as a surplus strip) included the $1.75M of dividends in the taxpayer's income on the grounds that s. 75(2) did not apply to a fair market value sale.

Masahura J granted the taxpayer's application for rescission of the dividends (with the monies apparently to be returned to New Integrated (per para. 56).) It was appropriate to apply Pitt, which allows for rescission of a "voluntary disposition" (such as the dividends) where there is "a mistake of sufficient causative gravity was made that would make it unconscionable, unjust or unfair to leave the mistake uncorrected" (para. 34). The "causative mistake" in this case was a mistake of law regarding s. 75(2) - and this mistake clearly had sufficient gravity given that "the tax implications were basic to the Plan" (para. 50).

After acknowledging the cautionary note in Pitt that rescission should not provide relief for artificial tax avoidance (para. 48), Masuhara J stated (at para. 57):

A key determinant in this case is the common general understanding as to the operation of s. 75(2) by income tax professionals and CRA as well as my finding that CRA would not have sought to reassess the Trust prior to Sommerer.

Agence du Revenu du Québec v. Services Environmentaux AES Inc.; Agence du Revenu du Québec v. Riopel, 2013 DTC 5174 [at 6466], 2013 SCC 65

Riopel Facts

Mr. Riopel was the sole shareholder of "JPF-1" and he and his wife (Ms. Archambeault) held 60% and 40% of the shares of "Déchiquetage." The parties intended to amalgamate the two corporations to form "JPF-2," with Mr. Riopel as the sole shareholder of JPF-2.

A detailed tax plan which was presented to Ms. Archambeault and Mr. Riopel on September 1, 2004, contemplated the sale by Ms. Archambeault of her shares of Déchiquetage to Mr. Riopel [sic, JPF-1?] in consideration for $720,000 to be satisfied by (a) a promissory note of $335,000 (corresponding to the ACB of her shares) and (b) the issuance of 385,000 Class C preferred shares with a redemption amount of $385,000. Shortly after the amalgamation, the promissory note would be repaid by JPF-2, and the Class C preferred shares would be redeemed with a view to the resulting deemed dividend being paid out of JPF-2's capital dividend account. However, the amalgamation in fact occurred before any sale by Ms. Archambeault, and the amalgamation agreement did not reflect Mr. Riopel as being the sole shareholder of Déchiquetage going into the amalgamation. The lawyer and accountant tried to fix these problems without alerting the clients, by having them sign revised documents to reflect a post-amalgamation s. 86 reorganization: they showed Ms. Archambeault's shares of Déchiquetage being converted on the amalgamation into common shares of JPF-2, and then they provided in the documents for the redemption of those common shares in consideration for the promissory note of $335,000 and the issuance of 385,000 preferred shares.

Both CRA and Quebec's Ministère du Revenu assessed Ms. Archambeault on the basis that she had received a deemed dividend of $335,000. The taxpayers then brought a motion seeking "recognition of the agreement they had actually reached [on September 1, 2004] so that the documents would reflect their true intention" (para. 13).

AES Facts

Preliminarily to a sale of a portion of its shares of a subsidiary ("Centre") to a new investor, AES and Centre instructed their advisors to implement a s. 86 reorganization of Centre, so that AES's voting shares of Centre were exchanged for (a) 4,500,000 voting participating shares with an aggregate paid-up capital of $1, and (b) a promissory note for $1,217,028. AES had erroneously understood that the adjusted cost base of its Class A shares of Centre was $1,217,029, so that the exchange would occur on a rollover basis. In fact, the ACB of those shares was only $96,001, so that the exchange gave rise to a taxable capital gain of $840,770. AES was reassessed accordingly.

After filing AES's notice of objection, the parties cancelled the $1,217,028 note and issued a $95,000 note and 1,122,029 Class C shares with a value of $1,122,029. They then asked the Quebec Superior Court for an order under art. 1425 declaring the effectiveness of these changes. Revenu Quebec contested the motion, and the Attorney General of Canada participated as intervener (in this case as well as Riopel).

Disposition

After noting (at para. 32) that "a contract is distinct from its physical medium," LeBel J found (at para. 36) respecting Riopel that "on September 1, 2004, the parties reached a verbal agreement to carry out a detailed tax plan, the essential terms of which had been recommended to them by their tax advisors," and (at para. 37) "the agreement of wills was not implemented properly." Respecting AES, "the admissions in the record confirm the existence of a tax planning agreement…[but] the agreement, the intended effect of which was to defer the tax payable was vitiated by the error made in calculating the ACB" (para. 39).

Respecting the Court's jurisdiction in a province where the common law of rectification did not apply, "the determination of the common intention, or will, of the parties represents a true exercise of interpretation" for purposes of art. 1425 C.C.Q. (para. 48). After indicating (at para. 54) that if all that had been established was "a taxpayer's intention to reduce his or her tax liability" then "absent a more precise and more clearly defined object, no contract would be formed," LeBel J. granted the requested relief under art. 1425 in both actions, stating (at para. 54):

These agreements provided, for the corporations in question, for the establishment of determinate structures that would, had they been drawn up properly, have made it possible to meet the objectives being pursued by the parties. The subsequent amendments did not alter the nature of the structures contemplated at the outset. All they did was amend writings that were supposed to give effect to the common intention, an intention that had been clearly defined and that related to obligations whose objects were determinate or determinable.

Juliar and Shafron

After referring to the argument of the Attorney General of Canada as intervener that the Juliar line of cases was inconsistent with Shafron and Performance Industries, LeBel J stated (at para. 55) that the cases before him were "governed by Quebec civil law and are not appropriate cases in which to reconsider the common law of rectification."

Kanji v. Attorney General of Canada, 2013 DTC 5058 [5824], 2013 ONSC 781

The taxpayer settled a family trust in 1992 with $5000, which was used to purchase shares in a business corporation. The family trust acquired a commercial property in 2004, and by 2013 the trust's assets were worth approximately $62 million. Because the taxpayer was a settlor, trustee and capital beneficiary of the trust, s. 75(2) applied to gains and losses from the initial $5000. Therefore, s. 107(4.1) applied to all of the trust's property, and the taxpayer could not have any trust property transferred to his children on a s. 107(2) rollover, so as to avoid a deemed disposition of the trust property in 2013 under the 21-year rule in s. 104(4). The taxpayer applied for a rectification order.

Brown J. declined to give the requested order. He stated (at para. 33):

In this proceeding the applicants bear the onus of demonstrating, on a balance of probabilities, that at the time Mr. Kanji settled the Family Trust he intended to structure the Family Trust in a tax efficient manner which would allow for a tax deferred transfer of the trust's assets to his children in the future and that a mistake was made which resulted in the trust indenture failing to give effect to that intention.

The taxpayer had not called former counsel to testify about his instructions in establishing the trust. Brown J. found that the taxpayer had not shown that his instructions to counsel had expressed such tax-deferral intentions, having said on cross-examination that he did not recall whether his instructions to "minimize tax" included instructions to defer tax.

.Mac's Convenience Stores Inc. v. Couche-Tard Inc., 2012 DTC 5118 [at 7149], 2012 QCCS 2745 (Queb Sup Ct), aff'd supra

The taxpayer paid a $136 million dividend to the non-resident corporate defendant when it was indebted to the defendant. This reduced the taxpayer's retained earnings, which limited the deductibility of interest payments it could make to the defendant by virtue of the thin capitalization rules in s. 18(4). The taxpayer applied for a rectification order to declare the dividend void ab initio and replace it with a payment effecting a reduction in capital in the defendant's favour.

Before denying the application, the Hallée J stated (at para. 87-88) [Tax Interpretations translation]:

...the request of MAC's entails more than a simple modification of a written instrument.

MAC's instead would replace a legal act (a dividend declaration) by other legal acts (a capital reduction) of a significantly different nature in order to obtain a more favourable tax treatment, and this would thereby entail rewriting fiscal history contrary to proper criteria.

FNF Canada Company v. Canada (Attorney General), 2012 NSSC 217

The applicant, incorporated by a U.S. corporation ("Fidelity National"), received $23,659,000 from Fidelity National in order to finance its business in Nova Scotia. The applicant purported to repay these amounts as a return of capital. However, Fidelity National had disposed of its shares of the Applicant to a wholly owned US subsidiary soon after incorporating the applicant, and was not a shareholder when the $23,659,000 was paid or repaid. The applicant sought an order to effect a retroactive issuance of shares (of an unspecified number, and apparently of the same class) to Fidelity National (apparently so that Fidelity National would be considered to have received some or all of the payment as a paid-up capital distribution on those shares).

Coughlan, J. dismissed the application. The applicants' and Fidelity National's financial statements indicated that the $23,659,000 was "contributed surplus," as defined in the CICA Handbook - Accounting, but contributed surplus is not equivalent to "paid-up capital" as defined in s. 89(1) of the Income Tax Act. Coughlan J. therefore concluded that "the applicants have not demonstrated on convincing proof the intention that Fidelity National's payment would constitute invested capital which could be repaid as a return of paid up capital" (para. 31).

The Juliar line of decisions was not mentioned in the reasons.

Orman v. Marnat Inc., 2012 DTC 5052 [at 6814], 2012 ONSC 549

The applicants and the respondents (which were corporations held by the applicants) were defrauded in a Ponzi scheme. The applicants took the position that the uncovering of the fraud revealed that previous amounts the respondents reported as interest payments were actually return of capital, and that payments to the applicants were corporate loans rather than bonuses. They sought an order to rectify the respondents' corporate records to reflect the actual nature of the payments.

Perell J. denied the motion because, at the time the documents were prepared, the applicants and respondents intended that the payments be on income account. He stated (at para. 42):

Rectification is concerned with mistakes in recording the parties' intent or purpose in their writing. It is not concerned about mistakes in the underlying purpose.

Nevertheless, Perell J. agreed with the taxpayers that the payments were a return of capital rather than income, and issued a declaration to that effect. However, citing a desire not to impinge on the Tax Court's jurisdiction, he made the declaration "without prejudice" to how the payments should be treated in tax law.

McPeake v. Canada, 2012 DTC 5042 [at 6770], 2012 BCSC 132

The petitioners were trustees of a family trust which had been formed in order to permit capital gains on any subsequent sale of the shares of the private company with which the trust had been settled to be allocated amongst the children beneficiaries, thereby multiplying the utilization of the capital gains exemption. Such a sale and allocation in fact occurred two years later. However CRA then assessed on the basis that as the father, who had settled the trust, was included as a beneficiary and had a reversionary interest in the shares, s. 75(2)(a)(i) applied to deem all the trust income to be attributed to the father, so that such income could not be allocated instead to the children beneficiaries. The trust deed was then rectified by order of the BC Supreme Court (with CRA not opposing on being notified of this rectification application) to correct these errors.

However, rather than reversing its assessments, CRA confirmed the reassessments. It informed the father and trust that it had identified further errors in the trust deed (namely, the father could become sole trustee and therefore have the power to direct the disposition of, or the beneficiaries in, the shares, so that s. 75(2) continued to apply on the basis of s. 75(2)(a)(ii) or (b).) The trustees applied for a second rectification of the trust deed, this time with the opposition of the Justice Department.

In allowing the application, Dorgan J found that the multiplication of the capital gains exemption was an objective of the trust that had been pursued from its inception, and that this finding of a specific intention was sufficient to allow rectification.

S & D International Group Inc. v. A.G. of Canada, 2011 DTC 5072 [at 5771], 2011 ABQB 230

The corporate applicant (S & D) carried on a real estate trading and development business. It had three directors, whose wives, the individual applicants, each held 25% of S & D's shares. The directors held the remaining 25% indirectly through other corporations. The directors sought to remove their wives as shareholders. Accordingly, the shares of the wives in S & D were purchased for cancellation in consideration for the transfer of lands of S & D to a corporation owned equally by the wives. Due to a mistake, a 100% interest in the lands was transferred to the wives' corporation rather than a 75% interest. The transaction had been effected on the basis that the fair market value of the lands was equal both to their adjusted cost base and the stated price at which the wives' shares were repurchased. CRA reassessed S & D on the basis that it had realized a capital gain as a result of the lands having a fair market value that was almost five times their adjusted cost base, and the wives on the basis that they had received a deemed dividend equal to the stated (much lower) repurchase price for their shares. Following these reassessments, the taxpayers purported to rescind the transactions, but their "cancellation agreement" was found not to be effective to eliminate the corporate capital gain and the deemed dividends. The taxpayers applied to the court for a rectification order.

Graesser J. found (at para. 83) that although, unlike Juliar, the parties did not have a common continuing intention to avoid tax (but, rather, were trying to insulate the wives from an investigation of S & D by the Alberta Securities Commission):

Equitable relief is always discretionary. I thus think it is artificial to interpret Juliar as requiring that the parties demonstrate that the mistake was a "primary and continuing objective of the applicants from the inception of the transaction". That circumstance might make the case for equitable relief stronger, but it is not a pre-condition to the court granting equitable relief if it had been necessary to a achieve a just result.

After also referring to Stone's Jewellery, Graesser J. then stated (at para. 98-99):

In both cases, and on scant evidence, the courts were prepared to infer that the transactions would not have proceeded in the manner in which they did, had the parties not been operating under mistake.

I think it is a reasonable inference to make here that if the directors had not mistakenly believed that the fair market value of the lands was equal to their adjusted cost base, or that the lands could not be transferred to the shareholders at their adjusted cost base without triggering a present gain, that the transactions would have been structured differently.

Graesser J. ordered that the transfer of most of the lands by S & D to the wives' corporation be set aside (so that there would only be a transfer of lands having a fair market value equal to the stated repurchase price for the wives' shares), that such shares be canceled and that the cancellation agreement be voided ab initio.

Bouchan v. Slipacoff, 2010 ONSC 2693,

The defendant and plaintiff held shares in an incorporated dental practice. In the course of a civil dispute, the defendant sought leave to plead rectification to restore a provision to their shareholder agreement that, because of an alleged clerical error, was missing from the final agreement. Hockin J. granted leave, but also allowed the plaintiff to plead that the rectification plea was outside of the two-year applicable Ontario limitations period.

Hockin J. noted that a rectification plea is a distinct cause of action (para. 7). Section 5 of Ontario's Limitations Act, 2002 essentially commences the limitations period from when the applicant knows or ought to know of a potential claim against the defendant. Hockin J. stated (at para. 11):

The issue, therefore, is whether Dr. Slipacoff had actual knowledge of the missing provision for more than two years before the motion to amend or in the absence of actual knowledge where the issue is due diligence or discoverability, whether more than two years before the motion, a "reasonable person with the abilities and in the circumstances" of Dr. Slipacoff ought to have known the provision was missing from the signed agreement.

TCR Holding Corp. v. Ontario, [2010] O.J. No. 1238, 2010 ONCA 233

The applicant resulted from several corporations being amalgamated in order that the tax losses of some of the predecessor corporations could be accessed. The application judge had concluded that a further corporation ("846") had been included in the amalgamation on the basis of a mistaken belief that it was a corporation without any liabilities whereas, in fact, it had given a guarantee to a third party. Accordingly, the application judge had set aside the amalgamation nunc pro tunc.

MacPherson, J.A. found that there was no basis for interfering with the findings of the application judge. The third-party holders of the guarantee submitted that if the true intention was that 846 was to be included in the amalgamation as a corporation without liabilities, the proper rectification order would have been to amend the amalgamation to reflect this intention (which would have been unlawful in light of the solvency requirements in the Business Corporations Act). In response, MacPherson, J.A. noted that broadly speaking, a superior court has all the powers that are necessary to do justice between the parties (i.e., it was not retricted to ordering rectification), and that this alternative equitable basis for the application judge's order provided a ground for the relief granted.

Stone's Jewellery Ltd. v. Arora, [2010] CTC 139, 2009 ABQB 656 (Alta QB)

A corporation ("Stone's") had entered into an agreement in 1996 to purchase lands for $500,000. The closing was substantially delayed, and when the purchase finally was completed in 2004, title was taken in the name of the shareholders of Stone's (the "Arora siblings"). By then, the lands had appreciated to a value of over $4 million. In 2006, after the lands had further appreciated, the Arora siblings transferred the lands to a sister corporation of Stone's pursuant to an agreement which stated the parties' intention to have subsection 85(1) apply. The purpose of this transfer was to avoid having to pledge Stone's other assets in project financings for the development of the lands.

The Minister assessed Stone's and the Arora siblings on the basis that in 2004 there had been an appropriation of Stone's beneficial interest in the lands by the Arora siblings giving rise to GST, the realization of gain by Stone's and a taxable shareholder benefit to the Arora siblings; and that the 2006 transfer did not occur on a rollover basis because the lands were inventory rather than capital property.

Strekaf J. found that rectification of the 2006 transfer was not an available or appropriate remedy, as the Court did not "have the power to direct that the 2006 Transfer proceed on a tax free basis pursuant to section 85 of the Income Tax Act in accordance with the parties' intentions" (para. 45). Similarly, rectification was not available with respect to the 2004 transaction as the Court was "not being asked to rectify the transaction back to its intended form, but to undo the transaction" (para. 68). Instead, Strekaf J. applied the common law of mistake as it applied to contracts to find that the 2006 transfer was void ab initio because it was effected under the mistaken belief of all the parties that it could be effected on a rollover basis; and the 2004 transaction also was void ab initio as it had proceeded on the basis of an (implicit) assumption by the parties that it would not have adverse tax consequences.

Strekaf J. also indicated that he would have been prepared to apply the Juliar case to rescind the two transactions, if they were not void ab initio under common law principles of contract law. He stated (at para 54):

...granting rescission in order to permit parties who intended to transfer assets on a tax free basis pursuant to section 85 of the Income Tax Act to avoid a transaction that does not accomplish the fundamental purpose of achieving a tax free rollover does not constitute any greater rewriting of history or opening of the floodgates than permitting the parties to rectify their transaction by issuing shares instead of promissory notes, in order to effect the transfer on a tax free basis as a section 85 rollover rather than pursuant to section 84.1 of the Income Tax Act, as was done in Juliar.

Aim Funds Management Inc. v. Aim Trimark Corporate Class Inc., [2009] O.J. No. 4798, [2009] GSTC 170, 64 DLR (4th) 261, 2009 CanLII 29491 (Ont. Sup. Ct. J.)

The Minister assessed the applicant, a mutual fund manager, on the basis that a payment to it by mutual funds of deferred sale charges received by the mutual funds from redeeming investors represented consideration for taxable supplies of services made by the applicant to the mutual funds. Perell, J. concluded, on the evidence, that the mutual fund manager and the mutual funds intended that these amounts were to be paid to the fund manager as reimbursement in whole or in part for brokerage commissions previously paid by the mutual fund manager when the investor had purchased his units in the mutual fund, and granted an order of rectification of numerous contracts to accord with the form requested by the applicant. He stated (at para. 58) that "the Applicant does not seek to rewrite a contract to rewrite contractual history; rather the Applicant is seeking to rewrite a contract that does not correctly write the contractual history".

QL Hotel Service Ltd. v. Minister of Finance, 2008 CanLII 15226 (Ont SCJ), briefly aff'd 2009 ONCA 715

A transfer of tangible personal property by an Ontario corporation ("1006") to a second corporation ("QL") would have been exempt from Ontario retail sales tax if QL were a wholly-owned subsidiary of 1006 at the time of the transfer.

The Court first found that the transfer in fact qualified for this exemption as QL should be regarded as having issued one common share to 1006 (in consideration for the transfer to it of intangible personal property) immediately before the transfer to it of the tangible personal property (in consideration for the issue by QL to 1006 of special Class A shares.) The Court went on to find that if the common share had not been issued before the transfer of the tangible personal property, it would have been prepared to grant the request to rectify the QL resolution for the issuance of the common share and special shares to provide that the common share was issued first (thereby accomplishing the common continuing intention of 1006 and QL for the transfer to qualify for the exemption.)

QL Hotel Service Ltd. v. Minister of Finance, 2008 CanLII 15226 (Ont SCJ), briefly aff'd 2009 ONCA 715

In a property tax dispute, counsel moved to couple the taxpayer's appeal with a rectification application, so that the rectification would serve as an alternative if the main appeal failed. Turnbull J. allowed the motion to go forward on the grounds that the Minister, the entity likely to be adversely affected by the requested order, was already a party to the appeal. The taxpayer won the main appeal; Turnbull J. also granted the rectification order.

Binder v. Saffron Rouge, 2008 DTC 6112, 2008 CanLII 1662 (Ont. S.C.J.)

The taxpayers were incorporating shareholders of a corporation. Although they realized at the time that a share issue in 2005 to a U.S. investor would cause the coproration to cease to be a Canadian-controlled private corporation (a "CCPC"), they did not realize that this change would disqualify their shares from the lifetime capital gains exemption. The taxpayers claimed that they would not have agreed to this share issue had they known of the result. In 2007, the investors agreed to retroactively reduce the share issue to a level that would restore the corporation's CCPC status. They applied to the court for a nunc pro tunc rectification order to that effect.

Hoy J. refused to give the order. The taxpayers and U.S. investor did not have a "common, continuing intention that the transaction be effected in a manner that would preserve the Applicants' capital gains tax exemption." Therefore, Juliar was inapplicable.

Re Columbia North Realty Co., 2006 DTC 6124, 2005 NSSC 212 (NSSC)

On two occasions, a Nova Scotia company ("Columbia") made cash distributions to its non-resident shareholder, purportedly as distributions of paid-up capital. However, the capital previously contributed by the non-resident shareholder had been received as contributions of capital rather than share subscription proceeds. Accordingly, the distribution was deemed to be a dividend and, therefore, was subject to Part XIII tax.

Columbia applied for an order permitting rectification of its share register to reflect the issuance of common shares retroactive to the contributions made to it by the non-resident shareholder. Further orders were requested to the effect that the cash distributions be treated as distributions of such paid-up capital (together with a consequential amendment to Columbia's Articles of Association).

Coughlin J. ordered that the Minister be given notice of the application in order to have an opportunity to make submissions to the Court.

Snow White Productions Inc. v. PMP Entertainment, Inc., 2005 DTC 5150, 2004 BCSC 604

As the common intention of the parties to agreements respecting the production of a movie was that it would be eligible for the federal film or video production services tax credit and the equivalent BC income tax credit, the court agreed to a rectification of the agreements to reflect a different party as the holder of the copyright. Burnyeat J. noted (at p. 5155) that the parties had intended from the outset to obtain the tax credits, and this was not a situation of their "now seeking rectification for the purposes of reordering their affairs so as to avoid a tax disadvantage".

Re Razzaq Holdings Ltd (2000), 11 BLR (3d) 157, 2000 BCSC 1829

In 1992 the two shareholders of a corporation purported to transfer a total of 100 Class A shares and 100 Class B shares equally to two holding companies. In fact, there were a total of 200 Class A, and no Class B, shares outstanding because a year previously an additional 100 Class A shares had been issued, and the Class B shares had been cancelled, without these 1991 transactions yet being recorded in the minute books. Burnyeat J. granted an order pursuant to s. 206 of the Company Act (BC) (which provided for the rectification of any omission, defect, error or irregularity that has occurred in the conduct of the business or affairs of a company), so that all the shares of the corporation were transferred to the two holding companies. He stated (at p. 163) that:

"As there is nothing before me to suggest that Revenue Canada is or would likely to be a creditor of Rassaq as a result of an improperly implemented s. 85 rollover, I am satisfied that it is not necessary to take into account the interests of Revenue Canada".

He also indicated that even if he were incorrect in applying s. 206, he was satisfied that the court had inherent equitable jurisdiction to rectify the written instruments in question.

Attorney General of Canada v. Juliar, 2000 DTC 6589, 50 OR (3d) 728, [200] O.J. 3706, 2000 CanLII 16883 (Ont CA)

The Court confirmed the decision of the trial judge, to rectify an agreement for the transfer by the appellants of half the shares of a company to a newly-incorporated holding company so as to reflect consideration that was treasury shares of the holding company rather than promissory notes, on the basis of the trial judge's finding that "the true agreement between the parties here was the acquisition of the half interest ... in a manner that would not attract immediate liability for income tax" and a finding that the parties would have chosen to receive shares but for the mistaken belief of the advising accountant that the transferred shares had full cost base. Austin J.A. stated that he agreed with the propositions appearing in an extended passage from In Slocock's Will Trust [1979] 1 All ER 358, at 361, 363 (Ch. D) including the statement therein that:

"If a mistake is made in a document legitimately designed to avoid the payment of tax, there is no reason why it should not be corrected ... . It would not be a correct exercise of the discretion in such circumstances to refuse rectification merely because the Crown would thereby be deprived of an accidental and unexpected windfall."

Amalgamation of Aylwards [1975] Ltd. (2001), 16 BLR (3d) 34, 610 APR 181, 2001 CanLII 32734 (Nfld. Sup. Ct. T.D.)

A Newfoundland corporation was amalgamated with what was thought to be a wholly-owned subsidiary in a short-form amalgamation. However, it was later discovered that the subsidiary had an individual holder of preferred shares.

Green, C.J. noted (at para. 41) that under the rectification doctrine the parties are "allowed effectively to restructure the transaction by using a different mechanism, provided of course, that the result obtained by the use of the new mechanism was in accordance with the original intention of the parties". After noting (at para. 43) that there was a "clear inference from the affidavit evidence that knowledge of the existence of the [preferred] shares would not have resulted in a decision not to proceed", and that the amalgamation instead would have proceeded by way of a long-form amalgamation that preserved those preferred shares, Green, C.J. ordered rectification of the articles of amalgamation as of the original date and time of the amalgamation to reflect the existence of the preferred shares.

Dale v. The Queen, 97 DTC 5252, Docket: A-15-94 (FCA)

The taxpayers neglected to have shares that purportedly were issued to them in 1985 added to the authorized capital of the issuing corporation. The Supreme Court of Nova Scotia provided a rectification basis in 1992 which validated the share issue in 1985 on a nunc pro tunc basis. The Minister maintained that a rectification order, applied for in 1988, could not change the taxpayer's status from 1985-87 for the purposes of the Income Tax Act.

In finding that the retroactive character of the rectification order should be respected for tax purposes, Décary and Robertson, JJ.A. found that a rectification order (within the jurisdiction of the court) does bind the Minister in respect of tax assessment. Such an order cannot be the target of "collateral attacks" that would undermine its effect. However, the justices also acknowledged (at p. 5257) that the law might recognize an exception to the rule against collateral attacks if a jurisdictional error complained of is "at the very least, self-evident and not a matter of further debate."

771225 Ontario Inc. v. Bramco Holdings Co. (1995), 21 OR (3d) 739 (CA), aff'g (1994), 17 OR (3d) 571 (Gen Div)

Ontario farm lands were transferred to a non-resident corporation for the purpose of utilizing losses of that corporation. However, it was subsequently discovered that because the transferee was a non-resident corporation the transfer was subject to land transfer tax at a very high rate (20%). The applicant sought a rectification order to substitute a resident corporation as the transferee in order to reduce the land transfer tax. Galligan J.A. that he was not prepared to exercise the court's discretion to relieve against mistake for two reasons. First, equity will not grant relief if an adequate legal remedy exists, and the Land Transfer Tax Act specifically gave the Minister of Revenue broad discretionary power to relieve against inequitable demands for the whole amount of tax. Second, "to do so would run contrary to the well-established rule in tax cases that the courts do not look with favour upon attempts to rewrite history in order to obtain more favourable tax treatment" (para. 9) and "an equitable discretion should not be exerised in order to allow a taxpayer to reorder her affairs so that she can avoid a tax disadvantage which she suffered under the Land Transfer Tax Act as the direct result of a deliberate decision on her part to obtain a tax advantage under the Income Tax Act (para. 13).

See Also

Prowting 1968 Trustee One Limited v. Amos-Yeo, [2015] EWHC 2480 (Ch)

In order that the life tenants of two trusts (the 1968 and 1987 settlements) could access a reduced rate of U.K. capital gains tax on a sale of shares of a company held by the two trusts, it was necessary that they have held 5% of the nominal capital and of the voting rights for one year prior to closing the sale. Accordingly, somewhat more than a year before concluding a sale of the company, they purchased 115,000 shares each of the company from the trusts (representing over 5% of the number of outstanding shares). However, due to a calculation error of the trusts’ advisor (Mr Cull), who overlooked the fact that some of the shares held in the company had a higher nominal value per share, the shares sold to the life tenants represented only 4.97% of the company’s nominal capital. HMRC indicated that it was content for the claimants to proceed with a rectification application without its involvement.

In granting an application to rectify the agreements for the sales to the life tenants to increase the number of shares sold, the Court stated (at paras. 29, 36, 38):

As Barling J in Giles, [2014] EWHC 1373 points out, the distinction drawn in this criterion is between a mistake as to the effect of a document and a misapprehension of what the fiscal or other consequences are of a document which does not in fact misimplement the parties' or donor's intention. …

[T]he parties' intention was that the defendants should receive…enough shares…to satisfy the ER requirements. …[T]hey left the precise calculation of the relevant number to Mr Cull, and he made a mistake in that calculation. …[T] herefore the claimants have shown a sufficient mistake to found the jurisdiction to rectify the agreements. …

[T]he parties to the agreements had a sufficiently specific intention which was not reflected in the agreements as executed by them. The fact that they left the precise number of shares to be determined by Mr Cull to decide does not prevent their intention from being sufficiently specific.

Kennedy & Ors v. Kennedy & Ors, [2015] BTC 2, [2014] EWHC 4129

The trustees of a family trust exercised an appointment in favour of beneficiaries including the settlor of the trust (Mr Kennedy). The transfer to Mr Kennedy (pursuant to clause 2(c) of the appointment) of the remainder of the trust fund consisted of cash, and of shares whose distribution triggered capital gains tax, notwithstanding that it was a fundamental feature of the planning that the appointment not give rise to such tax. Two of the trustees (Mr and Mrs Kennedy) did not realize that the appointment transferred such shares to Mr Kennedy, and the third trustee (Mr Sturrock, who also was the legal and tax advisor) was not aware that the trust no longer had available losses to shelter gain from the transfer of those shares.

In finding the tests in Pitt of rescission for equitable mistake were satisfied, Sir Terence Etherton found that if the trustees had not been so mistaken, they would not have executed the appointment with clause 2(c). Furthermore, there could be partial rescission, i.e., only of clause 2(c), given that it was "a self-contained and severable part of a non-contractual voluntary transaction," (para. 46) and such partial rescission was ordered. Conversely, no declaration could be made to strike down clause 2(c) only as regards the shares, as this would amount to rectifying that clause. Sir Terence stated (para. 43):

Rectification cannot be granted unless the wording or legal effect of clause 2.1(c) did not represent their true intention. Intention must be distinguished from motive. Mr Sturrock's intention… was that clause 2.1(c) should have the legal effect which it had, namely to vest the whole of the remainder of the trust fund in Mr Kennedy absolutely. His mistake was in thinking that, for purely factual reasons extraneous to the document itself, clause 2.1(c) would not give rise to a charge to CGT… .

Demers v. The Queen, 2014 CCI 368

The two taxpayers, who had been CN employees, were convinced by two promoters (the Lavignes) to transfer all the funds in their CN pension plans to self-directed RRSPs managed by the Lavignes, with most of the funds being lost. However, they withdrew some funds from the RRSPs. In 2008, they along with other investors obtained a judgment from the Quebec Superior Court which annulled their investment contracts with the Lavignes and awarded them damages.

In finding that this judgment did not render the amounts withdrawn from the RRSPs non-taxable, Jorré J stated (paras. 39-40, TaxInterpretations translation):

[T]he Superior Court recognized that the appellants had received the two amounts in question, as they were deducted from the amount invested in the calculation of the amount which the Superior Court ordered the defendants to pay to the appellant. … Consequently, the nullification pronounced by the Superior Court does not change the fact that the appellants received the amounts…in question and that they were amounts withdrawn from their respective RRSPs.

0741508 B.C. Ltd. and 0768723 B.C. Ltd. (Re), 2014 BCSC 1791

In 2011, the petitioners conveyed undeveloped B.C. lands to a limited partnership with an affiliated general partner. Due to failed communications, the partnership had not been registered for HST purposes, so that the exemption under ETA s. 221(2) from the obligation of the petitioners to charge HST was not available. The partnership then issued LP units to 163 outside investors and commenced developing the lands. In 2013, CRA assessed the petitioners for their failure to charge HST. The petitioners then entered into a fresh agreement to convey the lands to the partnership (which now was registered) subject to a condition that the previous conveyance be judicially rescinded.

After noting that Solle v. Butcher, [1950] 1 K.B. 671 (C.A.), which established the doctrine of equitable mistake, had been reversed in Great Peace Shipping Ltd. v. Tsavliris Salvage (International) Ltd., [2002] EWCA Civ 1407, [2002] 4 All E.R. 689 (C.A.), Loo J stated (at para. 73) that here "the CRA does not argue that the equitable doctrine of mistake is not available."

She rescinded the transfer. First, there was no adequate legal remedy. Because of BC's abolition of HST before the discovery of the problem in 2013, the partnership could only recover, under ETA s. 171(1), the federal (5%) portion of the HST payable by it to the petitioners (assuming no rescission), as the "basic tax content" of the lands excluded the provincial HST.

Second, the mistake went to the legal effect of the transactions rather than merely their consequences: "Here, the intention of the petitioners from the very outset and throughout was that the Partnership would be registered under the ETA and there would be no net HST/GST payable" (para. 99).

Third, the petitioners had "clean hands," notwithstanding that their failure to timely file HST returns meant their non-registration was not identified before the adverse B.C. change of law. As per Hongkong Bank of Canada v. Wheeler Holdings Ltd., [1993] 1 S.C.R. 167, at 188, the clean hands doctrine only applies when "the dirt in question on the hand, has an immediate and necessary relationship to the equity sued for."

Graymar Equipment (2008) Inc v Canada (Attorney General), 2014 DTC 5051 [at 6802], 2014 ABQB 154

The applicants were a limited partnership ("FRPDI") and the partnership's wholly owned corporation ("Graymar"). The implementation of a debt restructuring entailed a complex series of transactions which resulted in an increased subscription of FRPDI for Graymar shares and a corresponding increased amount of debt owing by FRPDI to Graymar. FRPDI failed to repay the loan by the end of the following year, and the Minister assessed the FRPDI partners under s. 15(2).

Brown J dismissed the applicants' request for a retroactive repayment of the loan (by way of set-off against a return of capital by Graymar). Brown J found that rectification was not available as the debt restructuring transactions had no tax avoidance motivation, and "belatedly recognized" adverse tax consequences were insufficient for rectification (para. 79). Before stating (paras. 68-69) that it was inappropriate to consider that tax avoidance is the inherent intention in all commercial transactions, Brown J stated (para. 66):

Juliar sits uneasily with Supreme Court's direction in Performance Industries and Shafron that rectification is granted to restore a transaction to its original purpose, and not to avoid an unintended effect. While, therefore, rectification is available in order to avoid a tax disadvantage which the parties had originally transacted to avoid, it is not available to avoid an unintended tax disadvantage which the parties had not anticipated at the time of transacting.

And at para. 72:

[T]o skate over the requirement, as Juliar does, of showing the intention underlying the original transaction – would effectively render CRA (and, by extension, Canadian taxpayers) the insurer of tax advice providers.

Giles (as administratrix of Hilda Bolton estate) v. Royal National Institute for the Blind & Ors, [2014] BTC 24, [2014] EWHC 1373 (Ch)

The claimant applied for rectification of a Deed of Variation which altered the provisions of the will of Hilda Bolton with a view to reducing the incidence of inheritance tax, pursuant to s. 142 of the Inheritance Tax Act 1984, which permitted the effecting a deed of variation within two years of the date of death in order to redirect gifts passing under a will. It was intended to vary Hilda's will by providing that a devise go directly to four named charities, rather than to her sister, who survived her by one year, and who (like Hilda) left the residue of her estate to the four charities. However, contrary to the apparent intention set out in a letter to the four charities, the Deed of Variation did not redirect to them the surviving sister's entitlement to Hilda's estate but instead only redirected to them a gift of the residue of Hilda's estate.

In granting an order of rectification (which was not opposed by HMRC), Barling J applied the four criteria for rectification in Racal Group Services Ltd v Ashmore [1995] STC 1151 (CA):

- There was convincing proof of error as the contemporaneous correspondence established that the Deed of Variation was intended to accomplish the surrender of the whole (and not just the residue) of Hilda's estate to the four charities.

- Having regard to "the distinction drawn…between a mistake as to the effect of an instrument, and a misapprehension of what the fiscal or other consequences are of a document which does not in fact misimplement the parties' or donor's intention" (para. 32), the Deed of Variation did not give effect to the intent in 1, and the objective of saving inheritance tax was not a bar.

- Specific intent to accomplish 1 was shown.

- Substantive rights would be affected by the order rather than there merely being the securing of a fiscal benefit.

Sheila Holmes Spousal Trust v. Canada (Attorney General), 2013 ABQB 489

The federal Minister assessed the settlor of the appellant trust on the basis that the trust's taxable capital gain and investment income were taxable in his hands because the trust was a sham or invalidly settled, or because s. 75(2) applied. The settlor then filed a notice of objection. The Minister, as agent for the Government of Ontario, issued alternative reassessments in respect of the trust's Ontario provincial tax liability on the basis of the alternative conclusion that the Trust, if valid, was taxable in Ontario, not Alberta. The trustee for the trust filed a notice of objection to this assessment. In dismissing an application to the Court to declare that the trust was valid, Nixon J adverted to the principle in Addison & Leyen Ltd v Canada, 2007 SCC 33 (CanLII), [2007] 2 S.C.R. 793, at para. 11 that "Judicial review should not be used to develop a new form of incidental litigation designed to circumvent the system of tax appeals established by Parliament and the jurisdiction of the Tax Court," and stated (at para. 66):

The only dispute with respect to the validity of the Trust is with the CRA in relation to the payment of tax.

Pitt v. Commissioners for HM Revenue and Customs, [2013] UKSC 26, [2013] WLR (D) 172

The claimant had settled the moneys received as damages for injury to her husband on a discretionary trust of which she and others were trustees. The death of her husband gave rise to an immediate inheritance tax, as the terms of the turst had failed to provide that at least half of the settled property was to be applied during his lifetime for his benefit (as in fact occurred).

On finding that the trust should be set aside on the grounds of mistake, Lord Walker noted (at para. 122) that the true requirement for rescinding a voluntary disposition such as a gift or settlement was

for there to be a causative mistake of sufficient gravity; and …[this] test will normally be satisfied only when there is a mistake as to the legal character or nature of a transaction or some matter of law which is basic to the transaction.

He further noted (at para. 132) that "consequences (including tax consequences) are relevant to the gravity of a mistake."

Racal Group Services Ltd. v. Ashmore & Ors., [1995] BTC 406 (CA)

A deed for payment of £70,000 to charity, although it was intended to comply with an income tax requirement that the payment be for a period which might exceed three years, was executed in terms that ensured that the period would not exceed three years. Peter Gibson L.J. accepted that there was an error in carrying out the intentions of the relevant executive of the taxpayer, but found that the evidence did not establish with the requisite clarity what was the executive's intention as to when the covenanted payments should be made. Accordingly, the trial judge was justified in refusing an order of rectification.

Downtown King West Development Corp. v. Massey Ferguson Industries Ltd. (1993), 14 OR (3d) 528 (Ont Ct GD)

Given that a lease as signed did not reflect the terms agreed to in the letter of intent and that a change to the terms of a right of first refusal was never discussed with the party whom such change might adversely affect, this was found to be an appropriate case for rectification.

St. Ives Resources Ltd. v. MNR, 90 DTC 1375 (TCC), aff'd 92 DTC 6223 (FCTD), briefly aff'd in turn at 94 DTC 6261 (FCA)

In refusing to recognize a price rectification agreement, Sarchuk, J. stated (p. 1378):

"Rectification is an 'equitable remedy' whereby one party to a contract seeks the court's intervention to rectify a written instrument which does not accurately reflect the terms agreed to orally by the parties prior to putting their agreement down in writing ... the remedy of rectification is not available to correct a mistaken assumption of fact. In other words there must be a literal disparity between the terms of the prior agreement and the terms of the written instrument."

Administrative Policy

Income Tax Technical News, No. 22, 11 January, 2002, Under "Rectification Orders".

18 November 2004 Memorandum 2004-008325 -

General discussion of the distinction between rectification of mistakes and retroactive tax planning.

18 February 1999 T.I. 982563

The comments in IT-378R, that the validity of an election may not be denied by a taxpayer once it is accepted by the Department, is applicable to other elections.

Articles

Joel A. Nitikman, "Rectification: Specific Intent? General Intent? What is the Test? – Part II", Tax Topics, Wolters Kluwer, No. 2274, October 8, 2015, p.1.

Test is one simply of true intention, not specific intent (pp. 3-4)

In Juliar,…[t]he key passages from the Court of Appeal are these:…

[I]t is possible, , even probable, that no one mentioned income tax throughout the nine or 10 months in issue. The plain and obvious fact, however, is that the proposed division had to be carried out on a no immediate tax basis or not at all. [emphasis added]

[T]his underlined sentence is a statement of the taxpayer's true or real or overall (however one wants to say it) intention whether it is a specific intention or a general intention is simply irrelevant.

Mihail Tartsinis v. Navona Management Company [fn 7: [2015] EWHC 57 (Comm).]

The application in this case was to interpret a contract and alternatively to rectify it. The contract was for the sale of shares. There was a dispute about the sales price. It concerned a complicated adjustment mechanism….

[T]aking into account the actual negotiations and the true intentions of the parties, the Court found that the contract should be rectified to delete the adjustment mechanism, as it was never really intended. The test, said the Court, was this:

As I described earlier, the essential function of the doctrine of rectification, as the law has long been understood, is to provide equitable relief in circumstances where the objective approach of the common law results in a document being interpreted in a way that does not reflect the actual intentions of its makers. [emphasis added]

In my view this is the correct test. It is also the Canadian test. Kraft Canada Inc. v. Pitsadiotis [fn 8: 2009 CanLII 9421 (ONSC).] is a case in which a pension deed was sought to be rectified; the Court held that it was dealing with a "unilateral" document, that is, a document that reflects the intention of only its maker, as unlike a contract there is no counter-party to the document. The Court stated the test as follows:

[23] English courts have held that the settlor of a unilateral instrument may seek rectification by proving that the instrument does not express the settlor's true intention. [emphasis added]

Once again, no reference to specific or general intent, merely the true intention.

Availability of rectification where negligence inconsistent with a requirement for specific intent (p. 4)

My last point is this: in Performance Industries Ltd. v. Sylvan Golf & Tennis Club Ltd. [fn 9: 2002 SCC 19 at paragraph 66.] the Court said: "I conclude that due diligence on the part of the plaintiff is not a condition precedent to rectification."

In my view, it is simply impossible to reconcile this statement with a "requirement" to prove that there was a specific intention to avoid the tax result that occurred. If there is no requirement for due diligence, it means that rectification is available even when there is a mistake — even a negligent mistake [f.n. 10. In both Kraft Canada, at paragraphs 64 and 66, and Thomas Hugh Bartlam v. Coutts & Co, [2006] EWHC 1502 (Ch.) at paragraph 11, the Courts granted rectification even though the mistake was caused clearly by a professional advisor's negligence. This also shows that the ruling in Bramco to the effect that the existence of an alternative legal remedy (suing the professionals) means that rectification cannot be granted was incorrect.] — in the tax planning. If one had actually intended to avoid a specific tax result, it is extremely unlikely that most rectification applications would be brought: they are all brought exactly because someone did not focus specifically on a particular tax issue.

Usually will be a true intention to avoid tax in rectification cases (p. 4)

…[When] an appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada is warranted; one can hope… that the Court will set the test straight: not the specific intention, not the general intention, but the true intention. In the vast majority of cases, the inference drawn in Juliar will be true: no tax or no deal. Based on such an inference, rectification should usually be granted.

Catherine Brown, Arthur J. Cockfield, "Rectification of Tax Mistakes Versus Retroactive Tax Laws: Reconciling Competing Visions of the Rule of Law", Canadian Tax Journal, (2013) 61:3, 563-98

Juliar line of cases (pp. 573-4)