Subparagraph 125(6)(b)(ii) [repealed]

Cases

The Queen v. B & J Music Ltd., 83 DTC 5074, [1983] CTC 50 (FCA)

Since the cumulative deduction account is stated to include "the corporation's taxable income" rather than "the corporation's taxable income while a Canadian-controlled private corporation", it includes taxable income earned by a corporation prior to becoming a Canadian-controlled private corporation. (Decided under the pre-1977 version of s. 125(6)(b)(i), but relevant to the later s. 125(6)(b)(ii).)

Subsection 125(1) - Small business deduction

Cases

Scandia Plate Ltd. v. The Queen, 83 DTC 5009, [1982] CTC 431 (FCTD)

Ownership of the shares of an alleged Canadian-controlled private corporation was not acquired by a Canadian resident from a Swedish company before the date of closing of the written agreement of purchase and sale, rather than on the earlier effective date of that agreement when an alleged oral executory agreement was in place. Accordingly, the requirement that the company have been a Canadian-controlled private corporation "throughout the year" was not met. Cattanach J. stated (at p. 5012): "[W]hen there is a preliminary contract in words which is afterwards reduced into writing, or where there is an executory contract to be carried out by a deed afterwards executed, the rights of the parties are covered in the first case entirely by the writing, and in the second case entirely by the deed." In addition, any evidence that the Swedish company held its shares as a trustee for the Canadian resident until the time of execution would not assist the taxpayer, because the test of control rests on registered ownership, not beneficial ownership, of the shares.

Administrative Policy

92 C.R. - Q.50

A corporation that is a trader in securities is entitled to the small business deduction.

85 C.R. - Q.56

Where a firm performs engineering activities in respect of a project both at its office in Canada and the foreign project site, only income derived from those engineering services that are rendered in Canada will qualify for the deduction.

IT-73R6 "The Small Business Deduction" 26 March 2002

5 ...In examining the ordinary dictionary meaning of these words, "incident to" generally includes anything that is connected with or related to another thing, though not inseparably, or something that is dependent on or subordinate to another more important thing. "Pertains to" generally includes anything that forms part of, belongs to or relates to another thing.

The courts have found that, in interpreting the meaning of "pertains to" or "incident to" in context, there has to be a financial relationship of dependence of some substance between the property in question and the active business before the property is considered to be incident to or to pertain to the active business carried on by the corporation. In addition, the operations of the business have to have some reliance on the property such that the property is a back-up asset that could support the business operations either on a regular basis or from time to time.

Articles

Perry Truster, "Expanding into the U.S", Tax for The Owner-Manager, Vol. 2, No. 1, January 2002

Ancillary business activities in the U.S., although not carried on through a permanent establishment there, will not give rise to income eligible for the Canadian small business deduction.

Durnford, "The Distinction Between Income from Business and Income from Property, and the Concept of Carrying on Business", 1991 Canadian Tax Journal, p. 1131.

Subsection 125(3) - Associated corporations

See Also

Deneschuk Building Supplies Ltd. v. The Queen, 96 DTC 1467 (TCC)

After the taxpayer had filed a form T2013 allocating the $200,000 business limit between it and another corporation, the Minister reassessed the taxpayer on the basis that the taxpayer, in fact, was associated with three other corporations rather than one other corporation and allocated only $65 of the $200,000 business limit to the taxpayer and without giving written notice that a form T2013 was required to allocate the $200,000 business limit. Five years later, the taxpayer and the three other corporations filed a form T2013 allocating the entire $200,000 business limit to the taxpayer after the other three corporations were statute barred.

Brulé TCJ. found that because the Minister (through his failure to give written notice) had failed to comply with s. 125(4), and because the forms T2013 initially filed by the two sets of corporations were invalid, the Minister was required to allocate the business limit as specified in the form T2013 filed five years later.

Subsection 125(4) - Failure to file agreement

Articles

Louis, "Family Trusts - Panacea or Ticking Time Bomb?", Canadian Estate Planning and Administration Reporter, August 2, 1994, p. 1

Description of various circumstances in which the use of discretionary trusts can result in corporations becoming associated.

Subsection 125(5.1) - Business limit reduction

Administrative Policy

21 January 2013 T.I. 2012-046881E5

In response to a query regarding the business limit reduction under s. 125(5.1) in a situation where a Canadian-controlled private corporation was associated with another corporation that was fully exempt from Part 1 tax under s. 149 (the "NPO"), CRA found that the limit reduction would be required to take the taxable capital of the NPO into account.

Subsection 125(7) - Definitions

Active Business Carried On by a Corporation

Administrative Policy

16 November 2004 T.I. 2004-008194 -

The activity of leasing portable trailers and equipment would not constitute carrying on a specified investment business as the trailers and equipment would not be real property.

14 September 2000 T.I. 2000-003012 -

A day trader who incorporated his business likely would qualify for the small business deduction.

Business Tax

Cases

Canadian Wireless Telecommunications Association v. Nanaimo (City), 2012 DTC 5131 [at 7250], 2012 BCSC 1017

Ehrcke J. found that a Nanaimo bylaw requiring a $30 charge be collected from cellphone users for each 911 emergency call was a tax rather than a regulatory charge, and therefore was ultra vires the city. Some mobile phone carriers were incumbent local exchange carriers ("ILECs" - in this case, Telus), who owned key network infrastructure. Each ILEC was required under CRTC rules to allow other carriers to access its network at a fair market price. These other carriers were called competitive local exchange carriers. Implementing the proposed fee would have required costly architectural changes to the wireless carriers' networks.

Applying the criteria in Lawson as to when a charge is a tax (in circumstances where it is not imposed under the authority of a legislature): the fee was clearly levied by a public body; the fee was enforceable in law it was essentially compulsory (CRTC rules made 911 service mandatory); and the fee was intended for a public purpose, because 911 service relates to public safety.

Canadian-Controlled Private Corporation

Cases

Kaleidescape Inc. v. MNR, 2014 ONSC 4983

In order to try to qualify a Canadian corporation ("K-Can'), which economically was a subsidiary of a U.S. corporation ("K-US"), as a Canadian-controlled private corporation, 100 special voting shares were issued to an employee trust whose settlor was K-Can and whose trustee was Computershare. The Deed of Trust contemplated that Computershare would take its direction, in voting its shares, from the CEO of K-Can, who was a U.S. resident. In response to a CRA position that this established non-resident de jure control of K-Can, K-Can obtained a rectification order to "clarify" that this clause was really referring to the settlor (i.e., K-Can) giving voting directions to Computershare.

Carole Brown J rejected a Crown argument that this rectification would do nothing to detract from the de jure control of K-Can by K-US in light inter alia of a unanimous shareholder agreement delegating all the powers of the board to the shareholders (of which only K-US was prepared to make decisions), stating (at para. 30) that "the Deed makes it clear that the decision-making body is the Board of Directors." See summary under General Concepts – Rectification and Rescission.

Price Waterhouse Cooper, Trustee in Bankruptcy of Bioartificial Gel Technologies (Bagtech) v. The Queen, 2013 DTC 5155 [at 6361], 2013 FCA 164

In the two taxation years in question, non-residents held 60%, then 70%, of the voting (Class A) shares of the taxpayer. However, provisions of the unanimous shareholder agreement (USA) divided the holders of the Class A shares into three groups (A, B and C), with each group only entitled to vote for a specified number of directors. Accordingly, the non-residents had the right to appoint only three of the seven directors, then subsequently four of the eight directors.

The Crown submitted that a USA (defined in s. 146(1) of the Canada Business Corporations Act as an agreement "that restricts...the powers of the directors to manage, or supervise the management of, the business and affairs of the corporation"), only includes clauses which so restrict the powers of the directors, so that the voting rights contained in this shareholders agreement should not be taken into account as they were not part of a USA. Before rejecting this submission, Gauthier JA had referred to para. 85(c) of Duha Printers, where Iacobucci CJ stated that, in determining whether a shareholder had "effective control" of a corporation:

[O]ne must consider ... any specific or unique limitation on either the majority shareholder's power to control the election of the board or the board's power to manage the business and affairs of the company, as manifested in either: (i) the constating documents of the corporation; or (ii) any unanimous shareholder agreement.

She then stated (at para. 53):

I therefore read Duha Printers as holding that once the conditions set out in section 146(1) of the CBCA have been fulfilled, the Agreement qualifies as a USA and the two types of restrictions described at item (3)(c) of paragraph 85 must be taken into consideration when determining who has de jure control of the Corporation.

Therefore, the taxpayer was a CCPC, and was eligible for enhanced investment tax credits.

The Queen v. Perfect Fry Co. Ltd., 2008 DTC 6472, 2008 FCA 218

The taxpayer, a Canadian-resident corporation, was wholly owned by a Canadian public corporation ("Perfect Fry") which, in turn, was controlled by a group of Canadian-resident individuals who acted in concert. In finding that the taxpayer was a Canadian-controlled private corporation, notwithstanding paragraph (b) of the definition, Sharlow J.A. stated (at para. 7) that the Court agreed with the Tax Court Judge that paragraph (b) applied "only in situations where a majority of the voting shares of a corporation are held by non-residents or public corporations but no person or group of persons has de jure control".

Sedona Networks Corporation v. The Queen, 2007 DTC 5359, 2007 FCA 169

An agreement under which a Canadian-resident private corporation ("Ventures") was accorded the right to exercise, in its sole discretion, the voting rights with respect to shares of the taxpayer owned by a Canadian bank subsidiary ("BMCC") as well as the right to acquire those shares in the case BMCC terminated the agreement without proper cause, and a general power of attorney executed by BMCC to allow Ventures to carry out management services on BMCC's behalf, did not give Ventures de jure control of the taxpayer. Given that such shares were controlled (indirectly) by the Bank (a public company) resulted in the taxpayer not qualifying as a Canadian-controlled private corporation. Malone J.A. also noted (in relation to some employee stock options) that the effect of s. 251(5)(b) was to deem such options to be exercised so that the shares were owned by the optionees for purposes of applying the mythical ownership test in the definition of Canadian-controlled private corporation.

Silicon Graphics Ltd. v. The Queen, 2002 DTC 7113, 2002 FCA 260

The taxpayer, which was a Canadian corporation with Canadian management, had effected a public offering of its common shares in the U.S. as a result of which 89% and 74% of its common shares were owned by non-residents in its 1992 and 1993 taxation years, respectively.

In finding that the taxpayer was not "controlled, directly or indirectly in any manner whatever, by one or more non-resident persons", Sexton J.A. found that the quoted phrase was synonymous to control by a non-resident person or group of non-resident persons, that "'control' necessitates that there be a sufficient common connection between the several persons referred to in that definition in order for there to be control by those several persons" (p. 7120) and that "the common connection might include, inter alia, a voting agreement, an agreement to act in concert, or business or family arrangements" (p. 7117). Here, there was no evidence of any common connection among the non-resident shareholders.

Respecting a submission of the Crown that a U.S. corporation ("Silicon U.S."), that had lent U.S $5 million to the taxpayer and made financial contributions for software development and marketing, whose founder was a director of the taxpayer and whose hardware was utilized by the taxpayer's software, exercised de facto control over the taxpayer, Sexton J.A. stated (at p. 7121) "that in order for there to be a finding of de facto control a person or group of persons must have the clear right and ability to effect a significant change in the board of directors or to influence in a very direct way the shareholders who would otherwise have the ability to elect the board of directors." Here, Silicon U.S. was merely protecting its interests as lender to the taxpayer, and Toronto management managed the taxpayer and annually prepared the slate of individuals to be elected to the board.

Parthenon Investments Ltd. v. MNR, 97 DTC 5343, Docket: A-514-93 (FCA)

All the voting shares of the taxpayer were owned by a Canadian corporation all of whose voting shares were owned by a U.S. corporation. All the shares of the U.S. corporation were owned by two Canadian-resident corporations.

In finding that the taxpayer was a Canadian-controlled private corporation, MacGuigan J.A. stated (at p. 5345):

"Control has about it a character of exclusivity, of finality, and cannot allow for two masters simultaneously. In the case at bar control rests, ultimately, in the hands of Canadian residents. We do not see an interpretation in terms of ultimate control as an addition of the word 'ultimately' to what would otherwise be a rule of plain meaning, but rather as emphasizing that the concept of control has necessarily latent within it the notion of ultimate control."

International Mercantile Factors Ltd. v. The Queen, 90 DTC 6390 (FCTD), aff'd 94 DTC 6365 (FCA)

A Canadian-controlled private corporation ("Rieris") held 25% of the common shares of the taxpayer and an additional number of Class A shares (which had one vote per share and were redeemable by the corporation at any time for 1¢ per share) which were sufficient in number to result in Rieris holding exactly 50% of the votes. The other issued shares of the taxpayer were held by two public corporations. The taxpayer was found not to be a Canadian-controlled private corporation in light of the fact that a majority of its board consisted of representatives of the public corporations and a provision in the by-laws which indicated that if a new board was not elected annually (which could be done only by a majority vote) then the existing board remained. Therefore, the public corporations had legal and effective control with regard to all major decisions of the taxpayer.

Scandia Plate Ltd. v. The Queen, 83 DTC 5009, [1982] CTC 431 (FCTD)

"The word 'controlled' as used in the context of the definition means de jure control and not de facto control."

See Also

Price Waterhouse Cooper, Trustee in Bankruptcy of Bioartificial Gel Technologies (Bagtech) v. The Queen, 2013 DTC 1048 [at 228], 2012 TCC 120, aff'd 2013 FCA 164 supra.

In the two taxation years in question, non-residents held 60%, then 70%, of the voting (Class A) shares of the taxpayer. However, provisions of the unanimous shareholder agreement (USA) divided the holders of the Class A shares into three groups (A, B and C), with each group only entitled to vote for a specified number of directors. Accordingly, the non-residents had the right to appoint only three of the seven directors, then subsequently four of the eight directors.

The Tax Court found that, as the Canada Business Corporations Act deemed any share transferee to be bound by a USA, it followed that, if all the non-resident shareholders had sold their shares to the notional particular person referred to in para. (b), that particular person would be subject to the same voting restrictions under the USA. The Crown did not challenge this point in the Federal Court of Appeal decision summarized above.

Perfect Fry Co. Ltd. v. The Queen, 2007 DTC 588, 2007 TCC 133, aff'd supra 2008 DTC 6472, 2008 FCA 218

Paris J. found (at p. 600) that paragraph (b) of the definition "was not intended to require an attribution of the ownership of shares of a corporation to a hypothetical shareholder in the case where all of the shares of the corporation are already owned by a single shareholder". Accordingly, paragraph (b) did not apply to a wholly-owned subsidiary of a public corporation whose ultimate control was by a group of Canadian resident individuals.

Avotus Corp. v. The Queen, 2007 DTC 215, 2006 TCC 505

A non-resident shareholder of the taxpayer, who owned one-half of the taxpayer's shares and, by virtue of being chairman, was entitled pursuant to the by-laws to have the casting vote in the event of a tie vote, thereby had control of the corporation within the extended meaning of s. 256(5.1) and also had de jure control by virtue of such rights. Paris J. stated (at p. 224) that "the legal effect of a casting vote provision in the by-laws would not be negated by Malone's alleged ignorance of the provision".

McClintock v. The Queen, 2003 DTC 576, 2003 TCC 259

The Minister took the position that the taxpayer ceased to be a Canadian-controlled private corporation on July 17, 1990 when it completed an initial public offering of its common shares through the NASDAQ stock exchange in the United States, as a result of which a majority of its shares were owned by non-residents of Canada. The Federal Court of Appeal had held in Silicon Graphics Ltd. v. The Queen, 2002 DTC 7112 that the taxpayer was an CCPC throughout its 1992 and 1993 taxation years. There was no evidence that the non-resident shareholders of the taxpayer acted differently in 1990 after July 17 than they did in 1992 and 1993. Accordingly, the taxpayer was not a CCPC after July 17, 1990.

Administrative Policy

6 May 2014 CALU Roundtable Q. , 2014-0523301C6

Does CRA accept Bagtech? After referring to the position in ITTN no. 44) that "unanimous shareholder agreements are not to be considered in applying paragraph (b) of the definition ‘Canadian-controlled private corporation'" in s. 125(7), CRA stated:

The interpretation that the CRA had given to the Duha case in the documents referred to above cannot be reconciled with the interpretation of that case by the Courts in Bagtech. In determining if a shareholder has de jure control, the CRA will adopt the views of the Court in Bagtech where appropriate in determining which shareholder or group of shareholders has "effective control" (paragraph 36 of the Duha case) or "long run" control (Donald Applicators Ltd. et al v MNR, 69 DTC 5122) of the corporation in light of the applicable provisions of the Act.

29 August 2000 Memorandum 2000-002318

After noting that a limited partnership with a sole general partner is generally considered to be controlled by that general partner, CRA indicated that a corporation, the voting rights of which were owned as to 1/3 by an individual and as to 2/3 by a limited partnership of which the general partner was a wholly-owned subsidiary of a public corporation, was controlled by the public corporation.

1 September 1995 T.I. 5-950393

Where a non-resident owns 60% of the voting shares of a Canadian private operating company, that company will not qualify as a Canadian-controlled private corporation because the non-resident has de jure control even if a shareholders' agreement requires that decisions on certain matters be taken only with the consent of at least 61% of the holders of the voting common shares.

8 December 1994 T.I. 5-941905

Provided the provisions of ss.265(5.1) and 251(5)(d) do not apply, two non-resident related individuals who each own 50 voting common shares of a Canadian private corporation, with a related-Canadian resident individual owning 100 voting preferred shares, will not cause the corporation to be a Canadian-controlled private corporation.

Income Tax Regulation News, Release No. 3, 30 January, 1995 under "Canadian-Controlled Private Corporation"

The control test envisages situations where over 50% of the shares of the corporation are owned by one or more non-residents or by one or more public corporations regardless of whether a controlling group can be identified.

11 September 1992 T.I. (Tax Window, No. 24, p. 15, ¶2202)

A corporation controlled by an individual who is a resident by virtue only of the sojourning rule in s. 250(1)(a) will qualify as a CCPC, assuming that the sojourn in Canada was primarily for purposes other than to obtain a tax benefit.

91 C.R. - Q.9

The ownership of all the common shares of the corporation by a trust all of whose beneficiaries are non-residents will not preclude the corporation from qualifying as a Canadian-controlled private corporation where the trustees are resident in Canada and they, in fact, control the corporation.

3 October 89 T.I. (March 1990 Access Letter, ¶1153)

s. 256(1.2)(c) relates to whether a corporation is associated, and therefore is not applicable for determining control for purposes of s. 125(7)(b).

3 January 1990 T.I. 5-9256 (Tax Window Files "'Meaning of Canadian-Controlled Private Corporation' - Control Test"

Where a Canadian-resident private corporation owns all the shares of a resident Canadian corporation ("N") which, in turn, owns all the shares of a Canadian corporation ("A"), A will not qualify as a Canadian-controlled private corporation because of the direct de jure control by N. The introduction of the concept of de facto control by the enactment of s. 256(5.1) did not eliminate the relevance of direct de jure control by a non-resident person.

Income of the Corporation for the Year From an Active Business

Cases

Borstad Welding Supplies (1972) Limited v. The Queen, 94 DTC 6205 (FCTD)

The taxpayer, which owned and operated an industrial gas and welding products business disposed of substantially all the working assets of that business other than refillable gas cylinders, which it retained and leased to the purchaser.

Before concluding that the lease payments were income from an active business, Reed J. first found that the payments were income from a business in light of the presumption that income earned by a corporation that is incorporated for certain business purposes is business income, and in light of the presumption (in s. 129(4.1)) that income from property that pertains to an active business is not income from property (which she interpreted as indicating that where there was any overlap between income from property and income from another business, the income fell into the business income category). Given this finding, it followed that the income was also income from an active business, because the definition of specified investment business excluded income from a business of leasing property other than real property.

Freeway Properties Inc. v The Queen, 85 DTC 5183, [1985] CTC 222 (FCTD)

The taxpayer company sold land as part of an active business enterprise. It was found that the sale probably would not have taken place if the taxpayer company had not taken back a mortgage. Given the close interdependence between the sale and the mortgage, interest received on the mortgage was active business income as well. (Pre-1980 provisions.)

Sedgewick Co-operative Association Ltd. v. The Queen, 83 DTC 5455, [1984] CTC 14 (FCTD)

"Income ... from an active business" in s. 125(1)(a)(i) refers to "income ... from a business" in ss.9(1), 18(1)(a) and 20(1)(u) and accordingly does not include the taxable capital gains of a co-operative association. (The distinction between active and non-active business income was not at issue.)

The Queen v. Rockmore Investments Ltd., 76 DTC 6156, [1976] CTC 291 (FCA)

The taxpayer, which had no full-time employees and made loans to potential borrowers referred to it by independent agents, was held to be engaged in an active business of lending money on mortgages. Jackett, C.J. stated that "each problem that arises as to whether a business is or was being carried on must be solved as a question of fact having regard to the circumstances of the particular case."

E.S.G. Holdings Ltd. v. The Queen, 76 DTC 6158, [1976] CTC 295 (FCA)

The circumstances of this case did not differ materially from Rockmore except that the business activities of the taxpayer were turned over to an agent. Jackett, C.J. held that there was no material difference between a corporation carrying on its active business "through the agency of officers ... and carrying it on through the agency of an independent contractor."

See Also

Muir Cap & Regalia Ltd. v. MNR, 91 DTC 533 (TCC)

The holding by the taxpayer of substantial term deposits for the future purchase of business premises was "only a collateral purpose ... and the withdrawal of the fund would not have 'a decidedly destabilizing effect' on the taxpayer's operations" (p. 536). Accordingly, interest on the term deposits did not pertain to and was not incident to the taxpayer's active business.

Newton Ready-Mix Ltd. v. MNR, 89 DTC 595 (TCC)

Funds that were surplus to the day-to-day requirements of the taxpayer's concrete business were invested by it in interest-bearing term deposits. Sarchuk J. stated:

"I am not satisfied that the evidence adduced establishes a financial relationship of dependence of some substance between the term deposits and the active business carried on by the appellant or that the appellant relied on the term deposits as an integral aspect of its business operations ... There is no cogent evidence as to the amount of cash reserves required on an ongoing basis, e.g., for truck replacement."

Similarly: Transport Lacté Inc. v. MNR, 89 DTC 606 (TCC)

Administrative Policy

7 March 2002 T.I. 2001-009178

in finding that cash accumulated to pay annual bonuses to the shareholder-managers was used in the corporation's active business and generated interest income that was income from an active business, CRA stated:

Generally, where a corporation has short-term cash reserves or near cash short-term investments as a result of accumulating cash in order to pay bonuses pursuant to the corporation's established policy, and the corporation actually uses the cash reserves and/or converts the short-term investments to cash in order to pay the bonuses, we would consider the cash reserves and/or the short-term investments to be active business assets.

CRA also stated:

...

2. Cash or near cash property is considered to be used principally in the business if its withdrawal would destabilize the business.

3. Cash which is temporarily surplus to the needs of the business and is invested in short-term income producing investments could be considered to be used in the business.

4. Cash balances which accumulate and are then depleted in accordance with the annual seasonal fluctuations of an ongoing business will generally be considered to be used in the business but a permanent balance in excess of the company's reasonable working capital needs will generally not be considered to be so used.

5. The accumulation of funds in anticipation of the replacement or purchase of capital assets or the repayment of a long-term debt will not generally in itself qualify the funds as being used in the business.

6. Cash or near cash property is considered to be used principally in the business if its retention fulfills a requirement which had to be met in order to do business, such as certificates of deposit required to be maintained by a supplier.

7. The CCRA recognizes that prudent financial management requires businesses to maintain current assets (including inventories and accounts receivables, as well as cash and near cash properties) in excess of current liabilities and will consider this requirement in assessing whether cash or near cash assets are used principally in a business. In the CCRA's view, cash and near cash assets held to offset the non-current portion of long term laibiliteis will not generally be considered to be used in the business.

19 July 1996 T.I. 5-960746 -

In determining whether X Co is a CCPC, where 20% of its shares are held a partnership whose general partner ('Genco") is controlled by a public corporation ("Pubco"), Pubco would be considered to have control over the voting rights attached to the X Co shares owned by the partnership.

14 July 1995 T.I. 5-950791

liclic

"As a general rule, income from a licensing agreement would not be income from an active business because it would be income from a source that is property or income from a specified investment business. In a situation where it could be established that the licensing income is related to an active business carried on by the recipient corporation or the recipient corporation is in the business of dealing in or originating the property from which the licensing income is received, such income could be considered to be income from an active business."

26 July 1995 T.I. 5-951469

"Where a financing arrangement that is fundamental to the business operations requires certain security to be maintained and it is reasonable to conclude from the facts that the security is employed and at risk in the business, the security may be considered to be used in the business. However, if there is no real expectation that the security will be resorted to, one could conclude that the security was not used in the business.

28 April 1993 T.I. 930165 (C.T.O. "Franchise Royalty Income - Active Business")

Discussion of whether lump sum payments received by a franchisor from its franchisees are income from an active business. "If no significant service is required or provided, this would indicate that the monthly royalties are income from property. On the other hand, the provision of significant services would indicate that X is carrying on a business."

92 C.R. - Q.50

Interest or dividend income derived by a corporation that is a trader in securities would pertain to or be incident to its active business.

29 June 1992 T.I. 920958 (December 1992 Access Letter, p. 25, ¶C117-178)

The return of surplus from a pension plan to the employer would constitute active business income provided that the employer's contributions to the plan were deducted in computing its income from an active business.

November 1991 Memorandum (Tax Window, No. 13, p. 14, ¶1584)

Funds which a CCPC raises by issuing flow-through shares which require the funds to be expended within 24 months on CEE, etc. will be considered to be used in an active business while invested in short-term deposits.

90 C.R. - Q56

Recapture of CCA which arises after cessation of a business will be considered to be income whose source is the business in which the asset was employed.

October 1989 Revenue Canada Round Table - Q.15 (Jan. 90 Access Letter, ¶1075)

In determining whether term deposits of a corporation which are required as collateral to obtain a line of credit are used in an active business, RC will consider the criteria illustrated in the Ensite case and will also consider the length of the term of the deposit, the reasonability of the amount involved, the necessity of the investment and the alternatives that could have existed.

October 1989 Revenue Canada Round Table - Q.17 (Jan. 90 Access Letter, ¶1075)

Where a corporation leases a building to its wholly-owned subsidiary that uses it in its business, with the result that the rent received by the parent is income from an active business by virtue of s. 129(6), recapture of depreciation arising on the sale of the building will be treated as income from an active business.

IT-73R4 "The Small Business Deduction - Income from an Active Business, a Specified Investment Business and a Personal Services Business".

Personal Services Business

Cases

Dynamic Industries Ltd. v. The Queen, 2005 DTC 5293, 2005 FCA 211

The sole employees of the taxpayer were its sole shareholder ("Martindale") who provided the services of an iron worker and construction manager, and his wife who provided administrative services.

The taxpayer did not carry on a personal services business given that it was remunerated on a cost-plus contract basis that was commonly used by subcontractors carrying on a business like that of Martindale, in previous years and subsequent years it had provided numerous services to enterprises other than the sole enterprise ("SIIL") to which it was providing services in the taxation years in question, Martindale was substantially independent of SIIL, and SIIL exercised no meaningful control over his activities.

See Also

C.J. McCarty Inc. v. The Queen, 2015 TCC 201

The taxpayer ("CJ") was a Canadian corporation owned by an engineer ("McCarty"), his wife and their daughter. CJ entered into a series of three "consulting contracts" with a third party ("MEG") for the provision of management services respecting a substantial construction project for hourly fees. In finding that CJ's business was not a personal services business, Lyons J noted that

- "there was no meaningful degree of control by MEG over Mr. McCarty's work activities" (para. 52) after accepting (at para. 51) the testimony of McCarty that "he was told to ‘go build it'…but was not told what to do nor how to accomplish the desired results."

- CJ could have worked for third parties but provided services solely to MEG because of the scale of the project and the demands on Mr. McCarty's time (para. 55) so that the services CJ provided were "not integral to MEG's business" (para. 57).

- Respecting chance of profit and risk of loss, an hourly pay scale was common in the business, there were no fringe benefits or stock options, there were sometimes significant delays in payments for CJ's services, there was an expectation of performing warranty work and there was a risk of being sued

9016-9202 Québec Inc. v. The Queen, 2014 TCC 281

Until 1995, a Quebec garbage collection company ("EBI") employed its garbage collectors and drivers. It then encouraged most of them to each become the sole shareholder and director of a newly incorporated Quebec company with nominal capitalization, so that EBI entered into contracts with each company for the provision of the services of the individuals which previously had been provided directly. These arrangements were terminated after CRA reassessed.

After stating (at paras. 59-60, TaxInterpretation translation) that "under Quebec civil law, the existence of a relationship of subordination is essential to finding a contract of service," and that "there is subordination if the payer has the ability to determine how the work is executed," Favreau J noted (at para. 62) that the Wiebe common law tests can be used in the Quebec context as they are non-exhaustive indicators of control.

Here, the individual companies carried on personal services businesses, so that the deduction of various expenses was properly denied. EBI exercised the same daily control of the individuals' activities after the change as before (and subsequently, after the new arrangements were terminated) through detailed daily reporting, detailed monitoring by its foremen and strict controls on how its trucks (which were owned by EBI) were utilized and parked – as well as the individual corporations themselves being administered by EBI's accountants for a fixed fee and having the same address as EBI. (The identity of the tasks performed before ad after also showed "integration.") There was minimal prospect for gain or loss (with the net income of the individual companies essentially the same as the employees' income previously) and with a prohibition against using EBI trucks for another company.

G & J Muirhead Holdings Ltd. v. The Queen, 2014 DTC 1067 [at 3009], 2014 TCC 49

The taxpayer was owned by its sole employee ("Muirhead") and his wife, and provided well inspection services to an arm's length corporation ("Harvest") under a services contract with it.

The taxpayer had a personal services business – but for the services contract, Muirhead would have been a Harvest employee. Muirhead had regular work shifts charged out at an hourly rate, and the taxpayer's provision of equipment (a truck that Muirhead also used outside of the job, personal tools, and flame-retardant clothing, but not key specialized tools) was not beyond what might reasonably be expected of an employee. Harvest was the only client, and Muirhead the only employee. Respecting the taxpayer's right to an overtime rate of an additional $17 per hour, Boyle J stated (at para. 31) that instead "clients and customers of a business normally seek to negotiate volume discounts, not volume surcharges."

The intentions of the parties to the services contract were irrelevant "as the personal services business provisions would be meaningless if the intention of the third party purchaser of the services (Harvest) and the individual's corporation ... in entering into their contract governed, as that contract can only be a contract for services" (para. 7).

Gomez Consulting Ltd. v. The Queen, 2013 DTC 1125 [at 670], 2013 TCC 135

Bédard J found that the taxpayer, wholly owned by an individual ("Almeida"), was operating a personal services business, given that:

- the taxpayer's compensation was limited to $69.33 per hour that Almeida worked;

- the taxpayer's two clients provided the tools; and

- Almeida was closely controlled by the clients, including that he could not choose where to work and that he reported to a team leader.

9098-9005 Québec Inc. v. The Queen, 2012 DTC 1284 [at 3864], 2012 TCC 324

The taxpayer's director ("Mr. Gitman") and his two sisters inherited equal interests in a number of rental properties and a business, which they held in a "de facto partnership." The partnership's properties and business were managed principally by the taxpayer, which was owned, operated and staffed solely by Mr. Gitman, in consideration for an annual fee of $150,000. The partnership was its only client. The taxpayer claimed small business deductions in three consecutive taxation years. The Minister denied the deductions on the basis that the taxpayer's management activities were a "personal services business" under s. 125(7), and therefore it was not engaged in an "active business carried on by a corporation."

Bédard J. affirmed the Minister's position. But for the existence of the taxpayer, Mr. Gitman would have been working directly for the partnership in a function that was an "office," given that he held "a subsisting , permanent, substantive position which had an existence independent of the person who filled it" for which he "was entitled to a fixed remuneration" (para. 48). Although it was "well established that a partner cannot be an employee in his own partnership" (given that the control of a partner in the partnership business is inconsistent with the subordinate character of the employment relationship) (para. 27), the same restriction did not apply here as "an 'office' ... does not require the individual to be in the service of some other person" (para. 28).

Peter Cedar Products Ltd. v. The Queen, 2009 DTC 1314, 2009 TCC 463

The principal salesmen and purchasing agents for a brokerage corporation whose business was transacting in cedar shakes and shingles established a partnership of which corporations of which they were specified shareholders were members, in order to continue carrying on these purchase and selling functions. In finding that the corporations did not carry on personal services businesses, Webb, J. noted that the individuals (through their corporations) were given significant latitude and independence with respect to the performance of the services and that the manner in which the partnership was compensated (a share of adjusted gross profits of the brokerage corporation) meant that the partnership had an opportunity for profit and the possibility of incurring losses. The fact that the individuals continued as directors of the brokerage corporation and therefore were employees, was not relevant to the question whether their corporations carried on personal services business in respect of the services provided by the partnership.

Robertson v. The Queen, 2009 DTC 679, 2009 TCC 183

The individual taxpayer was the sole shareholder of the corporate taxpayer ("RREL") which, in turn, provided the engineering services of the taxpayer to a corporation ("SRAL") of which RREL owned 25% to 30% of the shares. In finding that the corporation did not carry on a personal services business, V.A. Miller, J. noted that SRAL only became involved in the proposal after Robertson had acquired the engineering contract, that Robertson only worked on contracts that he had generated, that RREL's share of profits of SRAL was determined by the amount of money that he brought into SRAL and that the contract between RREL and SRAL did not require the individual taxpayer to work any particular number of hours.

489599 BC Ltd. v. The Queen, 2008 DTC 4107, 2008 TCC 332

The taxpayer was not carrying on a personal services business given that in addition to five full-time employees it had two part-time employees.

Carreau v. The Queen, 2008 DTC 3106, 2006 TCC 20

A corporation ("9043") of which an individual was the sole shareholder, officer and employee, and which was retained by a contractor of Hydro Quebec ("Sodéfi") to provide the services of the individual as a computer programmer to Hydro Quebec, was found to be carrying on a personal services business on the basis that, but for the existence of 9043, the individual would have provided services to Hydro Quebec as a subcontractor of Sodéfi and given that there was a relationship of subordination between the individual and Hydro Quebec that was sufficient to establish that under the Civil Code of Quebec the individual would have been viewed as an employee of Hydro Quebec. Although Hydro Quebec could exert little control over the way in which the individual conducted the work, given his level of skills and expertise, he nonetheless was subordinate on the basis of his mandatory presence at assigned places of work in accordance with a scheduled established by Hydro Quebec (in order that he could communicate with other Hydro employees) and in light of the imposition of rules of conduct on him (i.e., providing advance notice of any absences because of illness or taking leave).

W.B. Pletch Co. Ltd. v. The Queen, 2006 DTC 2065, 2005 TCC 400

The taxpayer was owned by an individual ("Pletch") and his wife. Pletch served as the president and then as vice-president and director of a company ("Thyssen"), and the taxpayer provided the services of Pletch to Thyssen for management fees. In finding that the taxpayer carried on a personal services business, Hershfield J. found that (given the flexibility of some of the arrangements between Thyssen and Pletch), some of the services of Pletch provided by the taxpayer to Thyssen could be characterized as advisory services, there was no allocation of the compensation paid to the taxpayer wearing its "advisory hat" and "executive hat", and that the services of the taxpayer had been merged into one source of income viz., compensation for performing the role of senior executive.

Galaxy Management Ltd. v. The Queen, 2005 DTC 1558, 2005 TCC 674

The taxpayer, through its key employee, provided sales and purchase services to two companies engaged in the manufacture of knitted garments and the supply of textiles and yarn. If the taxpayer did not exist, the individual could reasonably be regarded be regarded only as an independent contractor rather than as an employee of the two companies. The taxpayer bore the cost of equipment, its compensation took the form of commissions, the employee received no fringe benefits from the two companies, and he was not subject to any meaningful degree of control by them. Accordingly, the taxpayer did not carry on a personal services business.

S & C Ross Enterprises Ltd. v. The Queen, 2002 DTC 2078, Docket: 1999-4601-IT-G (TCC)

The sole shareholder ("Ross") of the taxpayer served as the CFO of a Canadian company ("Clearly Canadian") and also performed services on behalf of the taxpayer for Clearly Canadian. The taxpayer was found not to have a personal services business given that the compensation received by Ross from Clearly Canadian was for the running of clearly Canadian on a day-to-day basis and that the consulting fees paid to the taxpayer were for duties that normally consultants would have been hired to perform. In addition, the taxpayer rented at its own expense the necessary business tools from Clearly Canadian, incurred various operating expenses, did not obtain any limitation on claims for negligence that Clearly Canadian might make against it and obtained compensation (in the form of stock options) for services provided by it to third parties.

Bruce E. Morley Law Corp. v. The Queen, 2002 DTC 1547 (TCC)

The shareholder of the taxpayer, who previously had been a partner in a law firm providing, or supervising the provision of, the bulk of legal services required by a Canadian public corporation ("Clearly Canadian") became a vice-president in Clearly Canadian as well as the sole employee of the taxpayer. Thereafter, all the consideration paid by Clearly Canadian for the services of the taxpayer was satisfied by the payment of fixed monthly amounts to the taxpayer pursuant to a "legal services agreement".

Given the findings in Criterion Capital Corp. v. The Queen, 2001 DTC 921 (TCC), the taxpayer likely would have been successful in establishing that it did not have a personal services business if all administrative services had been provided by the individual in his capacity of vice-president of legal services, and all legal services had been provided by the taxpayer through its employee (the individual). However, the relevant agreements indicated that both administrative and legal functions had been transferred to the taxpayer, with the result that it provided administrative services that were to have been performed by the individual. Accordingly, the taxpayer carried on a personal services business.

Placements Marcel Lapointe Inc. v. MNR, 93 DTC 821 (TCC)

A business of providing construction cost appraisal services, which the taxpayer provided to a corporation through the services of its president and principal shareholder, represented a personal services business, given that such individual might reasonably be regarded as an employee of the recipient of the services.

Crestglen Investments Ltd. v. MNR, 93 DTC 462 (TCC)

An officer and specified shareholder of the taxpayer who provided services to a partnership through an office in her home would not have been considered an employee of the partnership in the absence of the incorporation of the taxpayer given the presence of remuneration risk (her remuneration was not determined until after the end of each year in which she performed the services), the inexactitude of that remuneration, and the fact that she provided her own workplace and provided her management skills without any direct controls on how she performed her tasks. Furthermore (p. 466):

[A] partner cannot be an employee of a partnership that is capable of entering into a contract of employment with the partnership and as a consequence an incorporated employee could not become an employee of a partnership [of which] the incorporated employee was a partner.

Société de Projets ETPA Inc. v. MNR, 93 DTC 516 (TCC)

The taxpayer, through the services of its shareholder, prepared advertising brochures and folders for various clients, and had the printing work done exclusively by a corporation ("Bourguignon") of which the shareholder previously had been styled an employee prior to the incorporation of the taxpayer. In the absence of the taxpayer, the shareholder would not have been an employee of Bourguignon given various indicia of an independent contractor including the absence of any control or supervision by Bourguignon, the payment of rent by the taxpayer to Bourguignon for the occasional use of a small office at Bourguignon's premises, the payment of often substantial sums by the taxpayer to Bourguingon for overtime or to speed up the production of certain projects in order to meet the taxpayer's business objectives, and the undertaking of other projects with other printers or with a printshop purchased by the taxpayer, following the termination of the business relationship between the taxpayer and Bourguignon. These factors outweighed the billing of the customers by Bourguignon alone (followed by the payment of a 10% commission to the taxpayer) and the fact that essentially the same relationship was described as one of employer-employee prior to the incorporation of the taxpayer.

David T. McDonald Co. Ltd. v. MNR, 92 DTC 1917 (TCC)

The voting preferred shares of the taxpayer were held by Mr. McDonald and its common shares were held by his wife and children. In finding that if the taxpayer had never existed, it would not be reasonable to regard Mr. McDonald as an officer or employee of a footwear distributing company ("Status") to which the taxpayer had contracted to provide consulting services, Mogan J. noted that in the years in question, Mr. McDonald was not working on a full-time basis for Status and the taxpayer was engaged in its own shoe distribution business selling to small retailers, Mr. McDonald was not under the control of any senior officer of Status but instead reported to a shareholder, and Mr. McDonald had enough experience, knowledge and goodwill to engage in the business of importing shoes into Canada on his own (i.e., he had the capacity to engage in the particular business on his own account).

533702 Ontario Ltd. v. MNR, 91 DTC 982 (TCC)

The taxpayer, which purportedly provided services to the third-party customers of the plumbing business of a corporation ("BPH") owned by the husband of the taxpayer's shareholder was found to provide those services instead to BPH given that the third-party customers were not even aware of the existence of the taxpayer and there was no other evidence to indicate that there was any contractual arrangement between the taxpayer and the customers. Accordingly, but for the existence of the taxpayer, its shareholders would have been an employee of BPH.

Administrative Policy

28 November 2010 CTF Roundtable Q. 21, 2010-0386361C6

CRA stated that para. 1(j) of IT-189R2 ("Corporations Used by Practising Members of Professions") and para. 17 of IC 88-2 ("General Anti-Avoidance Rule) are both correct in context and are not contradictory.

(IT-189R2 states that, in determining whether a corporation is carrying on a professional practice under s. 125, a relevant factor is whether the corporation pays the professional a reasonable salary in an employment relationship under a written agreement. IC 88-2 states that it is not an abuse under s. 245(4) for a corporation, for tax reasons, to decline to pay a non-arm's-length employee so as to avoid generating losses.)

Income Tax Technical News, No. 41, 23 December 2009

Under the "more than five full-time employees test", CRA accepts that the test is met when a corporation has five full-time employees plus one or more part-time employees.

2004 Ruling 2004-008431 -

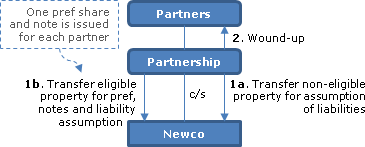

A professional partnership is converted to a Canadian-controlled private corporation ("Newco") pursuant to ss.85(2) and (3) and former partners provide professional services to the professional partnership, through corporations controlled by them (the "contracting companies"), with the resulting fees paid by Newco reducing its income to below the business limit. Ruling that provided that partners providing professional services to Newco through contracting companies would not, but for the existence of the contracting companies, be officers or employees of Newco in respect of those professional services, the contracting companies will not be considered to be carrying on personal services businesses.

90 C.R. - Q56

Recapture of CCA which arises after cessation of a business will be considered to be income whose source is the business in which the asset was employed.

1 February 1999 T.I. 982371

"It is generally the Department's view that a foreign corporation is a 'person' for purposes of the Act unless the context clearly indicates otherwise." Accordingly, for purposes of applying the personal services business rules, a Canadian corporation was found to be associated with a U.S. corporation that it controlled.

17 December 1996 T.I. 963605

A foreign corporation is a "corporation" and a "person" for purposes of the Act.

26 February 1991 T.I. (Tax Window, Prelim. No. 3, p. 5, ¶1128)

S.125(7)(d) does not require that the individuals be reasonably regarded as officers or employees of the corporation with respect to the services being provided by them to the corporation, but only requires that they may reasonably be regarded as officers or employees of that corporation. Accordingly, where the two individuals happen to be directors of the corporation in question and receive director's fees, it will not be possible for them to enter into an arrangement with the corporation under which their services are provided to the corporation through corporations owned by them.

11 September 89 T.I. (February 1990 Access Letter, ¶1122)

Opco, which has imposed a hiring freeze, nonetheless would like to engage services of Mr. A to complete a specific project over a 2-year period on a contract basis. Opco would provide him with an office and Mr. A would act quite closely with Opco's engineering staff, and Mr. A's corporation would be paid $7,000 per month over this period. In light of both the integration test and the control test, it is likely that his corporation would be considered to have a personal services business, and this conclusion likely would obtain even if his corporation derived through his services 50% of its consulting revenue from other sources.

IT-73R4 "The Small Business Deduction - Income from an Active Business, a Specified Investment Business and a Personal Services Business".

IT-168R3 "Athletes and Players Employed by Football, Hockey and Similar Clubs" under "Personal Services Business" and under "Endorsements and Public Appearances"

Articles

Michael Gemmiti, "Placement Agencies: Insurable and Pensionable Employment", Canadian Tax Highlights", Vol. 22, No. 3, March 2014, p. 10.

Source deduction liability of placement agency (p. 10)

A placement or employment agency is potentially liable to make contributions under the Employment Insurance Act (EI Act) and the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) for workers that it places with a client….

Subcontractor v. placement agency (p.11)

Occasionally, a company has argued that it was not a placement agency because it provided its clients with distinct services that included a worker and did not simply provide the worker. In OLTCPI Inc. (2010 FCA 74), the FCA suggested that this distinction was important "in insuring that the placement agency provisions not apply to persons, such as a subcontractor, providing services which require that workers attend to the premises of the client and perform functions, sometimes at the direction of the client." In several cases such as Dataco Utility Services ([2001] TCJ no. 372), Supreme Tractor ([2001] TCJ no. 580), and S K Manpower (2010 TCC 584), the TCC held that a company supplied something more than labour.

No source deduction liability where incorporated worker (p.11)

A placement agency need not deduct and remit EI premiums and CPP contributions if payments are made to a corporation (such as an incorporated worker) for services rendered. Neither the EI Act nor the CPP refers to an incorporated worker, but the CRA commented on this issue in TI 2000-0005305 ("Personal Service Corporations," April 10, 2000):

- Where a corporation carries on a personal services business, it is that corporation, rather than the corporation to whom services are being provided, that is required to withhold and remit (including the employer's share of EI and CPP) income taxes, CPP contributions, and, if necessary, EI premiums.

Thus, if it is commercially feasible to do so, a placement agency may limit its potential exposure under the EI Act and the CPP by placing incorporated workers.

Sophie Virji, "Old News, New Trend: Personal Services Business on the Rise", CCH Tax Topics, Number 2192, March 13, 2014, p. 1.

Ubiquity of oil field independent contracors (p.1)

[O]il and gas producers…have often outsourced their oil field work to corporations owned by the contractors. In this regard, such contractors would typically have their own liability insurance and workers' compensation coverage through their corporations, thereby minimizing the administrative burden, among other things, for the producers. Further, such a model is conducive to the cyclical nature of the industry…

Unusually high level of control in Muirhead (p.3)

The facts in Muirhead Holdings are somewhat unique in regards to the control Harvest exerted over the taxpayer. Producers will typically not have this much control over independent contractors and their corporations. However, many other facts are similar to those found in oil field service corporations. In terms of the applicability of this decision to Albertans in the midst of tax litigation on the issue of PSBs, one of the criteria is the number of sources a corporation receives work from. From the Court's analysis in Muirhead Holdings, it appears that if Muirhead Holdings had more than one source of work, the chance of profit and risk of loss factors may have fallen in his favour, given the potential requirement to pick and choose between jobs depending on their profitability.

Specified Investment Business

Cases

Weaver v. The Queen, 2008 DTC 6517, 2008 FCA 238

The taxpayers each owned 25% of the shares of a Canadian-controlled private corporation ("SRP") that headleased reserve land from an Indian band and subleased lots to members of a retirement community, who had purchased manufactured homes from SRP for occupation on their respective lots. In determining that the business of SRP was a specified investment business, so that a sale of their shares in 1998 was not eligible for the enhanced capital gains exemption, Sharlow, J.A. noted (at paras. 25-26):

The definition of "specified investment business" does not ask about the general nature of the business of a corporation, or the degree of activity or passivity actually required by that business. Rather, it asks about the legal character of the income that the business is intended principally to earn. ... It is not relevant that SRP carried on an active business before that time. The fact is that on December 10, 1998, almost all of the income of SRP was rent, and almost all of the property of SRP was property that generated and could generate only rental income."

Baker v. The Queen, 2005 DTC 5266, 2005 FCA 185

Six individuals employed as custodians for the purpose of providing cleaning services to tenants of the taxpayer, and who worked from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. from Monday to Friday, for a total of 20 hours per week, did not qualify as full-time employees. Noël J.A. noted (at para. 14) that the term "full-time" was used in contra-distinction with "part-time" employment, and that "four hours a day fall short of the normal working hours of each day" (para. 16).

Lerric Investments Corp. v. The Queen, 2001 DTC 5169, 2001 FCA 14

The taxpayer, which employed two full-time employees directly, also had fractional co-ownership interests in eight apartment projects which also employed full-time employees. Applying the same fractional percentages to those latter full-time employees, the taxpayer had 5.05 full-time employees. In finding that the taxpayer carried on a specified investment business, Rothstein J.A. stated (at para. 17) that the definition "simply conceives of a single corporation employing more than five full-time employees", that "there are no words in the provision that imply that a proportional or sharing approach of the same employee by different employers is contemplated" and that "no co-owner or joint venturer can say that it individually employs the employees or portions of the employees".

He also stated obiter (at para. 18) that the test could be satisfied by employing five full-time and one-part time employee.

See Also

0742443 B.C. Ltd. [R-Xtra] v. The Queen, 2014 DTC 1208 [at 3811], 2014 TCC 301

The taxpayer, which had two employees including its shareholder, carried on a storage unit rental business.

Before referring to the "principal purpose" test and stating (at para. 26) that "whether we substitute ‘main' or ‘chief' or primary' or ‘51%', it comes down to an objective determination of what the payor was paying for," C Miller J noted that the taxpayer provided additional services free of charge, mostly respecting assistance in moving items into or out of storage, and stated (at para. 20) that he was not satisfied that "they are indeed core to what customers were paying for." Respecting a submission (at para. 27) that there was no difference with "the motel customer paying for a room", he indicated that even a small motel would be expected to provide additional services, such as utilities (e.g. phone, electricity, Internet), daily room cleaning, linens, parking and amenities, and then stated (at paras. 28-29):

Every hotel customer has an expectation of a bundle of hotel services in addition to the use of a furnished room. I have not been convinced that every customer seeking storage space has any greater expectation than the space itself and not an expectation of a bundle of services equivalent to hotel accommodation.

There is a tipping point where the provision of services overcomes the provision of property. … [A] few services to a few customers does not change the inherent nature of income from property.

The taxpayer was carrying on a specified investment business.

R&C Commrs v. Lockyer & Anor (for Pawson Estate), [2013] UKUT 050 (Tax and Chancery Chamber)

The deceased taxpayer and her three children held equal interests in a bungalow ("Fairhaven"), which they rented out as a holiday property. The Inheritance Tax Act provided that, when the taxpayer died, she would be exempt from inheritance tax on the Fairhaven interest if it was "property consisting of a business or interest in a business," but that this exemption did not apply where the business consisted "wholly or mainly of ... making or holding investments." The estate contended that the taxpayer's active management of the business meant that the business was not mainly the holding of an investment. The taxpayer's activities included having the property maintained and cleaned, advertising, and decoration, as well as continually re-letting the property (virtually all stays were two weeks or less).

The Upper Tribunal reversed a finding by the First-tier Tribunal that the investment business exclusion did not apply. As the taxpayer's interest thus represented an investment business, it was subject to inheritance tax. Henderson J. stated (at para. 42):

...I take as my starting point the proposition that the owning and holding of land in order to obtain an income from it is generally to be characterized as an investment activity. Further, it is clear from the authorities that such an investment may be actively managed without losing its essential character as an investment....Accordingly, the fact that the Pawsons carried on an active business of letting Fairhaven to holidaymakers does not detract from the point that, to this extent at least, the business was basically one of an investment nature.

Although the providing of "additional services" such as the provision of a cleaner, heating and hot water, television and telephone, and being on call to deal with emergencies, were not part of the maintenance of the property as an investment:

The critical question, however, is whether these services were of such a nature and extent that they prevented the business from being mainly one of holding Fairhaven as an investment. (para. 45)

The answer was negative (at para 46):

[T]here was...nothing to distinguish it from any other actively managed furnished letting business of a holiday property, and certainly no basis for concluding that the services comprised in the total package preponderated to such an extent that the business ceased to be one which was mainly of an investment nature.

Nagille v. The Queen, 2009 DTC 1103 [at 564], 2009 TCC 139

The taxpayer who was the sole director and officer of a corporation ("Alland") owned by him and a family trust, lent money in order for Alland to participate over the course of 15 months in what the taxpayer thought were purchases of inventory by another corporation ("Trev Cor"), with Alland to receive a share of the profits from resale of the inventory. In fact, Trev-Cor was engaged in a pyramid scheme so that few or none of the transactions actually occurred. Given the active involvement of the taxpayer in determining whether Alland should participate in the transactions and the fact that the transactions were found to be joint venture transactions with Trev-Cor, Alland was not engaged in a specified investment business, so that the losses sustained by the taxpayer on his loans to Alland were business investment losses.

Lee v. The Queen, 99 DTC 925, Docket: 97-3124-IT-G (TCC)

A corporation whose business was the operation of a 68-pad mobile home park on land which it owned was found to be carrying on a specified investment business notwithstanding the high level of service and superior maintenance standards which it offered to the tenants. Its clear purpose was to derive rental income from the tenants who occupied the pads.

Ben Raedarc Holdings Ltd. v. The Queen, 98 DTC 1218, Docket: 95-1844-IT-G (TCC)

Margeson TCJ. found (at p. 1225) that janitors "who worked all or substantially all of four hours per day, five days a week, throughout the years in question" would qualify as "full-time employees", but went on to find that there was insufficient evidence that there were more than five such full-time employees for those years.

Rogers v. The Queen, 97 DTC 890 (TCC)

A corporation that derived virtually all its income from the rental of a shopping centre owned by it was found to be engaged in a specified investment business. Bell TCJ. noted (at p. 892) that the "jurisprudence distinguishing income from business and income from property is of little or no assistance here" and that the definition of specified investment business "sets up an entirely new test, namely, whether the principal purpose of the business is to derive income from property". Accordingly, it was not relevant that, in the absence of this definition, the corporation might be considered to derive income from a business rather than income from property. Consequently, the shares of the corporation were not qualified small business corporation shares.

Canwest Capital Inc. v. The Queen, 97 DTC 1 (TCC)

A sum of $5 million was injected into the taxpayer with a view to being utilized in leasing activities. The portion of the sum that the taxpayer was unable to so deploy and instead invested gave rise to Canadian investment income for purposes of s. 129(1).

Crompton v. The Queen, 96 DTC 1700 (TCC)

A corporation owned by the taxpayer and his wife that did a high volume of trading in securities on the Vancouver Stock Exchange was found to be a small business corporation. The fact that the gains and losses were reported on capital account was not sufficient to justify a conclusion that the transactions were on capital account.

The Queen v. Hughes & Co. Holdings Ltd., 94 DTC 6511

A practising lawyer who spent approximately 28 hours per year on telephone calls monitoring the business of the taxpayer in addition to making occasional visits to the taxpayer's office in consideration for annual remuneration from the taxpayer of $8,250 did not qualify as a "full-time employee".

Strayer J. also found that the reference to "more than five full-time employees" meant "at least six" full-time employees.

Mayon Investments Inc. v. MNR, 91 DTC 364 (TCC)

The business of the taxpayers which consisted of providing mortgage financing on the security of second, third and fourth mortgages was found to be a specified investment business given that the number of full-time employees engaged by each of the taxpayers during the relevant taxation years did not exceed five.

Administrative Policy

23 January 2008 Memorandum 2007-0258011I7

Aco, a Canadian-controlled private corporation, holds rental apartment complexes, and an interest in a partnership (between it and two related individuals) to carry on the business of property management of Aco's properties, in which it employs more than 5 full-time persons. In finding that Aco's business is a specified investment business, CRA stated:

where a corporation carries on a business as a member of a partnership, employees working for the partnership are the employees of its partners collectively, but not of any of them individually. Accordingly, for the purpose of determining whether Aco's rental operations are a SIB, Aco is not considered to employ the employees of the partnership of which it is a partner, since such employees are considered to be employed by the partners collectively.

26 March 2001 T.I. 2001-006392 -

A corporation whose only business was the purchase of accounts receivable from an associated corporation at a discount and the collection of those receivables would generally be considered to be earning income from an active business rather than income from property and, therefore, would not be considered to be carrying on a specified investment business.

21 February 2001 T.I. 2000-0047815

A property management corporation also hold a minority interest in several partnerships whose only activity is holding rental property. The taxpayer acts as property manager for some of the properties held by the partnerships, while other properties are managed by third parties.

In determining whether its income from the rental partnerships was income from a specified investment business, CRA indicated that although each full-time employee of a particular partnership will be considered to be a full-time employee of each corporate partner, "each partnership must be considered separately when determining whether a partner's income is from a specified investment business."

19 January 1998 T.I. 5-983095

A pawnbroker fees would be considered to be interest for the purpose of determining whether a pawnbroker business is a specified investment business.

26 September 1997 T.I. 972291 [income from copyrighted music]

"If a company is in the business of composing music, the income it earns with respect to its copyrighted music would generally be considered active business income ... . Where the copyrighted music owned by the company was not produced directly by the company but rather relates to music composed by an individual who was not in the employ of the company at the time of its copyright, it is a question of fact whether the royalty income received by the company in any particular year is from a specified investment business or an active business carried on by the company."

9 October 1996 T.I. 962919 (C.T.O. "Specified Investment Business")

The leasing of taxi licences to arm's length parties is a specified investment business unless there are more than five full-time employees.

17 July 1995 T.I. 5-950413

"In the case of a corporation which carries on a business involving tennis courts and has a weight/exercise room the extent of the services it provides (e.g., availability of tennis and exercise instructors of professionals, organization of activities, availability of change rooms and a lounge) would be a significant factor in determining whether it is carrying on an active business or a specified investment business. ... [W]here the use of the tennis courts and weight/exercise room and all other services are available to members in consideration for membership fees and per use charges, the corporation would generally be considered to be carrying on an active business."

31 March 1995 T.I. 5-950121 -

"It is our opinion that normally a full-service motel operation would be providing a sufficient level of services such that it would not be considered to constitute a business whose principal purpose is to derive income from property. With respect to the campsites for trailers and campers, we have previously taken the position with respect to a corporation having less than six full-time employees, operating a trailer court and offering no more than normal services such as grounds maintenance and snow removal, that it would be considered to be conducting a specified investment business."

27 March 1995 T.I. 943010 (C.T.O. "Specified Inv. Bus.")

No relief is provided in the situation where, for a portion of the year, there are only five full-time employees rather than six.

14 July 1994 T.I. 5-941149 -

A partnership having less than six full-time employees that is engaged principally in providing rental spaces for mobile homes and offers no more than normal services such as grounds maintenance and snow removal will not be considered to be conducting an active business.

24 March 1994 T.I. 5-940124

A taxpayer that rents storage facilities to clients who use the facilities to store raw materials used by them in their manufacturing activities likely would be considered to carry on a specified investment business given that the associated services of unloading the raw material when received from the clients, and loading them onto a transport truck or a train when the client requires the materials, would be considered to be ancillary to the main objective of renting storage facilities.

3 March 1994 T.I. 5-933293

Although offering a motel, with rooms rented on a daily basis and services provided, will be an active business, it will be a specified investment business during the winter months if the rooms are rented on a monthly basis with no provision of services, and (during the winter months) there are fewer than five full-time employees.

4 February 1994 T.I. 932524 (C.T.O. "Small Business Corporation")

In applying the five full-time employee test with respect to a partner's income from the particular partnership, each full-time employee of the particular partnership will be considered to be a full-time employee of each corporate partner.

91 C.R. - Q.31

Where a corporation has more than five full-time employees, whether interest income is derived from a specified investment business will turn upon the factual question whether the employees were employed in the particular business giving rise to the interest income (including, a factual question as to the number of businesses carried on by the corporation), and on whether the interest income arose from a business or from property.

21 August 1991 T.I. (Tax Window, No. 8, p. 18, ¶1400)

Where a corporation provides rental storage facilities and a moving operation, it is a question of fact whether it is conducting an active business or two separate businesses one of which is a specified investment business.

26 June 1991 T.I. (Tax Window, No. 4, p. 25, ¶1316)

Where a corporation employs three employees in its real estate rental operation and three more who are licensed real estate brokers, it is a question of fact whether the brokerage activities are part of its rental business.

26 February 1990 T.I. (July 1990 Access Letter, ¶1332)

Generally speaking, royalty income is income from property. However, where it is incidental to an active business carried on by the recipient corporation or the recipient corporation is in the business of developing the property from which the royalties are received, such income would not normally be considered income from property. "Principal" is synonymous with the words "chief" or "main".

19 September 89 T.I. (February 1990 Access Letter, ¶1123)

A corporation which conducts a seasonal business which employs 10 to 15 employees for six months and 2 or 3 employees for the rest of the year will not be considered to employ 5 full-time employees.

11 September 89 T.I. (February 1990 Access Letter, ¶1123)

Where a corporation which is one of a group of corporations in the business of leasing rental properties employs a 7-man maintenance crew which spends 40% of its time working for the corporation and the rest of the time working for the associated corporations in return for a management fee, the corporation will not be considered to employ 5 full-time employees.

Where a corporation in the business of leasing rental properties employs 6 people in various functions, approximately 60% of whose time is spent on corporation business and the remainder on contract work for associated corporations, the corporation will not be considered to employ 5 full-time employees.

88 C.R. - Q.51